The Sovereign’s Parade at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, April 2023.

Sandhurst is home of the Royal Military Academy, where the British army trains its officers corps. The RMA’s motto is ‘Serve to Lead’ and it enjoys a proud, storied history of producing outstanding military officers. Of course, being the leadership academy of a deeply hierarchical and bureaucratic organisation, Sandhurst also occasionally turns out dullards, yes-people and General Melchett-types whose ambition far outstrips their ability. I say this not out of any sense of animus. I say this because it’s inevitable. Armies are made of humans and humans are fallible.

As long as I can remember, people have argued (including the sort of MPs who find themselves tumescent at the idea of national service) the police needs a good old-fashioned officer corps. They’d sort plod out! Get them stood by their beds! The idea’s more durable than a port stain on a regimental tie. I’m going to call it the the ‘Sandhurst Fallacy.’

I recently wrote an article for ‘UnHerd’ on police leadership failures and the rape gang scandal. Inevitably, in the comments, the Sandhurst Fallacy resurfaced with a vengeance. There really is a deeply-held belief struggling civilian police services, made up of pusillanimous working-class oiks, need nothing more than an injection of stiff-upper lipped army officers to rescue them from perfidy. So I thought I’d write about this idea (frequently discussed in police stations, usually informed by ex-squaddies who’ve enjoyed a rather more granular experience with ‘Ruperts’).

Why do I think it’s a fallacy? Police leadership, after all, is hardly in rude health. Then again, HM Forces are hardly immune from poor leadership and social justice mania either, but I digress.

The Russians are coming, but not before we’ve had bratwurst. My average summer as an undergraduate in the late 1980s and early 90s. They’re still using those FV432 carriers, by the way.

At this point, I suppose I should mention my totally undistinguished military ‘experience.’ My ironic Andy McNab-style Substack profile photo, of me on Salisbury Plain circa 1990, is a nod to this period of my life. More Andy McStab, geddit? (army in-joke). However, it’s relevant, because it partly informs my view of The Sandhurst Fallacy. For about six years, from the late 80s to early 90s, I was an army reservist (what used to be called the ‘Territorial Army’, which on occasion resembled a heavily armed drinking club). I genuinely enjoyed the experience, even if I didn’t choose to become a regular soldier.

As an undergraduate, I was paid to spend my summers schlepping around Salisbury Plain or unglamorous parts of North-western Germany, sometimes attached to regular units. After a stint as an infantryman, I was catapulted to the rank of lance corporal (but only because I transferred to the Intelligence Corps, where everyone starts as a lance corporal). I’ve therefore had brush contact with marching around, saluting and taking orders from terrifyingly confident young lieutenants with names like Rory and Sebastian. I know many serving and former soldiers. I’ve had a glimpse of the regular army, up close, warts and all.

So please bear this in mind when I say this:

Sandhurst Fallacy believers seem oblivious to a simple point - the British police service is an unashamedly civilian organisation. It was expressly designed to be as unmilitary as possible (even police ranks, sergeant excepted, were given non-military titles). To not resemble the yeomanry, who’d hitherto kept law and order with sabre and musket.

It’s why (cue nostalgic Hovis-ad type music) I think British police were once the best in the world, as opposed to jackbooted, machinegun-toting European-style gendarmes. You know, shouting ‘papers!’ and patrolling barbed wire fences with snarly Alsatians.

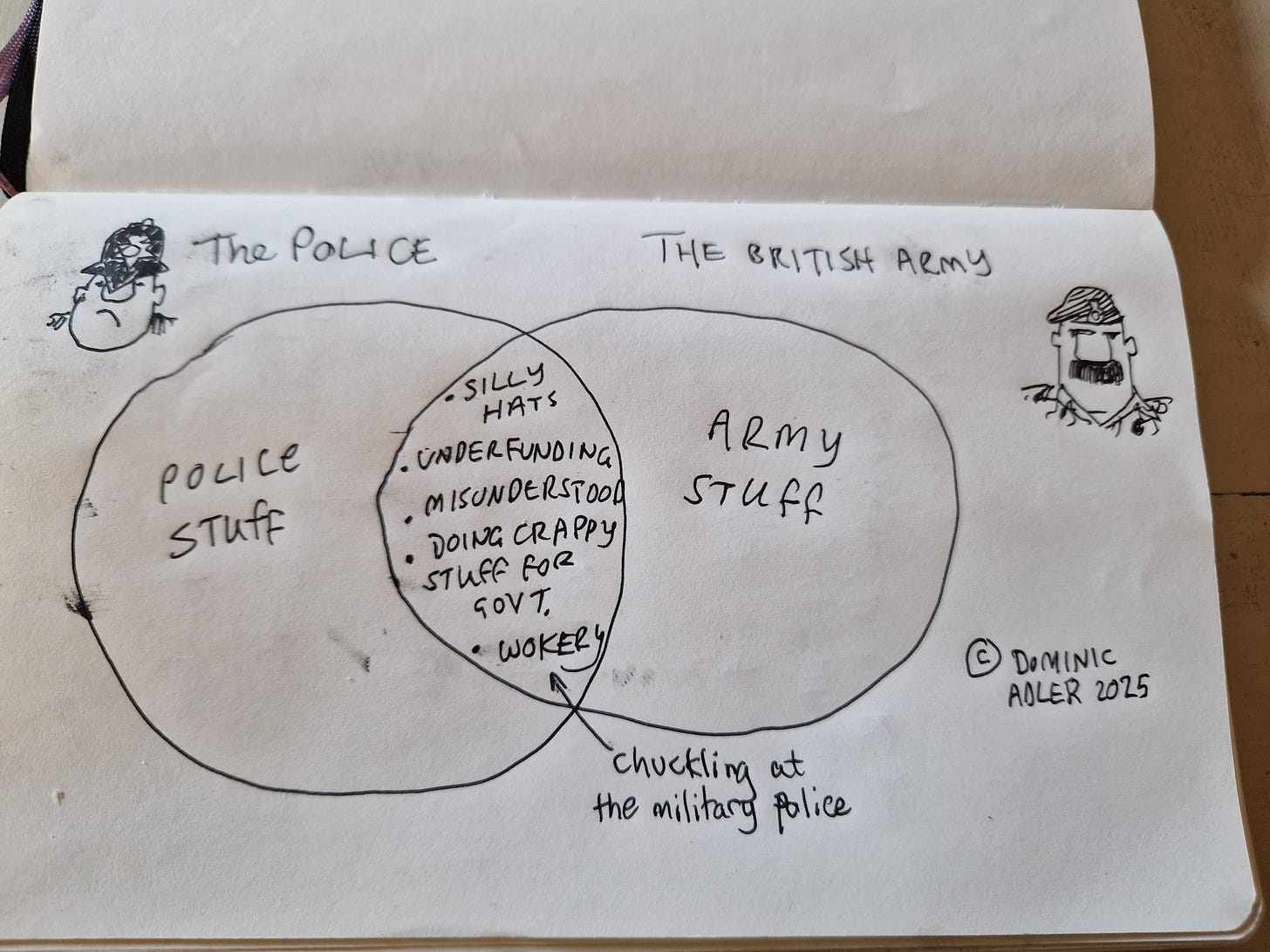

Yes, there are a few superficial similarities between the police and the military. Please note the words ‘few’ and ‘superficial.’ To prove the point, here’s my peer-reviewed and totally scientific Venn diagram on the subject:

Oi! Don’t complain about the quality of the graphics, this Substack’s free.

In fact, if you delve into history, you’ll see how the Metropolitan Police was once heavily influenced by the armed services. It wasn’t the army, though - it was the Royal Air Force. And the Met experimented with an officer corps, too.

In 1931, Lord Trenchard was made Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. Trenchard was a former army officer instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force. In those days it wasn’t unknown for former military officers to be made chief constables, which probably explains the origin of the Sandhurst Fallacy.

Generally speaking, Trenchard’s tenure was a Good Thing. He abolished the ponderous beat system of fixed patrols. He established police section houses. He set up the police college at Hendon (this unglamorous northwest London suburb has a long association with the RAF), until it was destroyed by The Avengers. Hendon was intended to be the Met’s equivalent of Sandhurst, turning out ‘Trenchard Men’ who’d assume the rank of inspector upon graduation. I’ve written about this before, albeit in the wider context of the contemporary police promotion snake pit system.

Suffice it to say, ‘Trenchard Men’ are the reason why black and white movies portray detectives as well-spoken chaps in fedoras, usually accompanied by a gruff cockney sergeant wearing a bowler hat. Incidentally, the cockney sergeant would carry the detective inspector’s forensic bag, which is where the term ‘bagman’ comes from (now used for staff officers and other flunkies). This, of course, was tied up with notions of class - it worked reasonably well in the not-very-meritocratic, class-conscious 1930s. And, having seen the Brigade of Guards up close, there are still parts of the army cosplaying the social mores of the period.

What doomed the Trenchard system was the Second World War; a significant number of policemen volunteered for the military and performed well (irony alert - the police briefly provided outstanding leaders for the armed services). Come the end of the war, many ‘Trenchard Men’ were faced with a choice; to continue a career as a colonel in Singapore or Hong Kong, with servants, polo and gin and tonics… or return to a blitzed-out London as a duty inspector.

Tough call, eh?

There’s a lesson here for the 21st century. The police has no officers mess. No battle honours or regimental silver. There’s little or no glory. The uniforms are ugly. The job has negligible social status. Or even tanks. Whisper it - might the lack of thrusting ex-officers attracted to policing be due to the grubby mundanity of the job?

1946: Major Hamish Bufton-Tufton, MC, explains to the Governor of Rajpoot why he’s in no hurry to return to Hackney for early turn.

At this point, one might nonetheless point out the military-style Trenchard system had merit. Wasn’t it proof of concept? Leadership’s a transferable skill, isn’t it? Surely it stands to reason some organisations, by virtue of role or circumstance, might turn out better leaders than others?

These are good points, although the contemporary police experiment with direct-entry senior officers has been (to put it politely) something of a curate’s egg. Including this example, where an ex-military officer hardly covered himself in glory.

Which brings me to the primary difference between coppers and soldiers; rank and operational independence. Giving an order to Pc Snooks is, theoretically, very different from giving an order to Corporal Snooks. At the end of the day, the primary operational decision made by the organisation - to arrest - is made by a constable. The lowest rank. Yes, police officers must follow ‘lawful orders’, but the decision to arrest is theirs and theirs alone. They are empowered with discretion. They are not only expected - but obliged - to reasonably question orders and instructions to test their lawfulness.

This is a luxury (understandably) denied a platoon commander in Basra, ordering Cpl Snooks to flank left with 3 Section. Now! This should hardly need explaining, but for adherents of the Sandhurst Fallacy, one mindset seems to map across to the other.

Can military officers make outstanding police officers? Of course they can (and do). Is this because they were military officers? Possibly, but not axiomatically. I’ve met ex-army officers who’ve joined the police. Some were (to use an army expression) complete choppers. I’ve met stars, too, people who happily took ‘demotion’ from captain to humble police constable. They used the qualities gained from their military service to progress. Should they progress quicker, though? Quite possibly. Although I’m not sure the modern police service, as currently constituted, would know how to utilise their qualities.

I’ll offer an example of this difference. Many years ago, military officers attending the advanced command and staff course would spend a week shadowing civilian emergency services. This helped attendees develop their knowledge of what’s called ‘MACA’ (Military Assistance to the Civil Administration) in times of emergencies such as terrorist attacks, natural disasters and industrial disputes.

An army officer (I think he was a colonel) spent a couple of shifts in the back of our police car. He was a terrific guy, witty and intelligent. When we were dealing with the public, he simply watched and kept his mouth shut. Played the ‘Grey Man’ (a virtue in the military).

The thing he found surprising, he said, was our independence of action. ‘You just spent eight hours doing your thing without any reference to your chain of command,’ he said. ‘You’re constantly making decisions I’d expect senior our NCOs to make.’ Our shift was typical - attending 999 calls, a bit of stop and search, referring people to other social services and squaring up scrotes who needed their fortunes reading. I remember we evacuated a tube station during an IRA bomb threat, which he found quite impressive (there were two of us with a length of tape). That involved updating the duty officer (an inspector) with what we were doing, rather than waiting for orders. ‘Okay, crack on, let me know if you need anything,’ the inspector replied.

In short, the army officer was impressed with how we operated autonomously, using commonsense and discretion (when it was still allowed). It meant we were able to deal quickly and efficiently with multiple tasks without referring constantly to our managers. ‘My soldiers are great, but I’m not sure how I’d compare your role with theirs,’ the colonel concluded at the end of the shift, shaking our hands.

Quite. Apples and oranges, right?

On the other hand, soldiers are capable of putting up with shit that’d make most coppers throw a hissy fit (I include myself in this). The sheer tenacity, resilience and stoicism of the British squaddie is genuinely amazing. It’s their superpower. If you could bottle it and sell it? You’d be richer than Elon.

These guys are often the best of us.

So, to proponents of the Sandhurst Fallacy, I’ll say this about comparisons between the army and police; Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's (I’ll let you decide which one is which).

A civilian police service demands officers from all backgrounds. One of the best detectives I knew was a former bus driver. I worked with an outstanding financial investigator who, after leaving school at fifteen, was a handyman. And yes, one of the most impressive inspectors I knew was a former parachute regiment officer. I’m not an expert on organisational culture, but I’m sure the police has much to learn from the army. As long as we Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s.

The biggest problem?

Policing doesn’t know what it is anymore. How can it identify what its leadership cadre should look like? Yes, there’s a macho fantasy to be had, one where we parachute a bunch of rufty-tufty army blokes into the police and sort the country out. I can imagine retired colonels - and the odd corporal - getting misty-eyed at the prospect, sitting at their keyboards, slagging off the woke Old Bill. But that’s all it is.

A fantasy.

It won’t survive (forgive the military analogy) first contact with the ‘enemy’, because we’re civilian coppers. We’re not really meant to have ‘enemies.’ Just people who’ve broken the law, who we’re meant to put in front of a court without fear or favour.

Now, parade dismissed. Please, Sergeant, carry on.

This is an interesting article. My 36-year career in the Royal Hong Kong Police and Hong Kong Police, which operates a direct-entry inspector scheme for inspectors, has given me a critical perspective on policing models. The Hong Kong scheme involved nine months of full-time training, including Cantonese for the expats, and a three-year probationary period before advancement to the full inspector rank. The Hong Kong policing model, derived from the old Irish Constabatory Colony model, is unique in its command and control structure and less autonomy for the individual constable. While the model has evolved over the decades, it retains these distinctive elements. The Hong Kong Police also retain a paramilitary role, undertaking many functions that the military would do in other jurisdictions. My experiences on overseas attachments in several police forces, including in the UK, have led me to believe that no model is perfect, as the clowns can still rise to senior ranks.

It seems to have been a mantra amongst the RW press that the armed services can sort anything out and the go to answer for any problem in the public sector is to bring in an ex-army officer. I don't for a moment doubt the competency of the lower ranks and the small unit leaders but lets face it, leadership and management at the strategic level in the armed forces seems to be less than optimal, look at the procurement crises and other problems that have beset the armed forces recently. The same press also do not grasp that the army and police fulfil quite different functions.

Still, since the press seem particularly unhinged at the moment expect more guff like direct entry to come out.