Trenchard House, circa 1993

Today’s article was partly prompted by my growing fascination with psychogeography (bear with me), being the relationship between the built environment and our sense of place. About how places make you feel and why.

For most police officers, the places they work don’t generally lend themselves to positive vibes; Oh look, that’s where I got my jaw broken. Ah, that’s where I picked up the malicious complaint that ran for three years. Hey, remember the especially putrid corpse we found in those flats?

This lead me, for some reason, to thinking about writing an article on The Job and belonging. About how, once upon a time, being a police officer meant becoming part of something bigger than yourself. People who know me from those days will probably be laughing now. Yes, I was a heretic gobshite when I was in the Job (I really was), but only because I loved it. Because I belonged, even when I didn’t want to. I don’t tend to get upset about things I don’t care about.

As I wrote about belonging, one of the things on my list was how paternalistic the Job used to be. The Met occasionally felt omnipotent; it could easily put a roof over your head if you needed it. It even paid some of your mortgage or rent.

And so I give you a story of belonging and its tragic decline, presented via the medium of housing. This Substack is nothing if not occasionally random.

There’s been an ongoing debate around where police officers should live - and be recruited from - for years. Should coppers be identifiable, next-door-neighbour types in every community? Or, as a sweaty old Pc once put it, ‘you don’t shit where you eat.’ Which, I think, was his way of saying you can’t really do ‘Heartbeat’ cosplay in Tower Hamlets or Stoke Newington. Well, not unless you have armoured doors and windows for when your punters find out where you live. And over half a million quid in the bank to buy a tiny flat for the privilege. I know many politicians and pundits might find this surprising, but police officers have families they’d prefer to shield from the realities of their day job.

Shocking, I know.

It should also be remembered more than a few overseas police services - especially those with gendarmeries or national forces - deliberately posts its officers miles away from home. Why? Well, if it comes down to it, coppers find it easier to baton-charge people they don’t know. Or less likely to be offered bribes or have their families threatened. I think I might have written before about how, on a trip to Paris, a gendarme asked me for directions. He was from faraway Marseilles and didn’t have a clue where he was. It was quite entertaining, the pair of us parleying in Franglais with a Paris A-Z.

When I joined the Metropolitan Police there was a clause in my contract which said, more or less, ‘The Commissioner of the Metropolis directs all constables shall live within a 25-mile radius of Charing Cross’. This mapped to the radius of the-then Metropolitan Police District (MPD). Charing Cross (where the top of Whitehall meets Trafalgar Square) has traditionally been the Capital’s official centremost point. There’s a fun history why in this article.

Confusingly, the MPD back then included semirural parts of the home counties outside Greater London. These faraway outposts of empire included exotic locales such as Epsom, Slough Staines and Elstree. You’d meet ‘London’ coppers who’d spent entire careers patrolling the urban hellscape of Esher. (Corrected, pocketbook rules apply here!)

This changed in 2000 or thereabouts, when London was gifted a mayor. This administrative oddity corrected, the relevant home counties forces were given the old Met police stations. Naturally, they sold them and pocketed the cash to spend on carrots, speed cameras and wheel clamps for tractors.

I digress. The 25-mile rule existed because the Commissioner wanted his officers living within a reasonable distance in case of grave emergency. Which makes sense. I don’t think the idea of coppers living in the communities they served was a big part of it, to be honest. When I joined, the Met was full of non-Londoners who lived as far away from their divisions as possible. When I told colleagues I was born within the sound of Bow Bells they gave me a strange look. I was a local. Even if I hadn’t lived in London for a while before I joined.

London is the most balkanised city in the UK, a place of either the rich or poor - key workers such as police, nurses and teachers don’t stand a chance of getting on the property ladder

Even back then, London was a prohibitively expensive place to live. To address this, we were paid an accommodation allowance on top of the usual London weighting. For married officers, this was about five hundred quid a month when I joined (yay!) but, due to government cheese-paring, was still five hundred-or-so quid when I retired 25 years later (boo!). I was lucky, in the mid-90s they got rid of it completely for new officers. Then they came for our pensions. Although the housing market, you’ll be amazed to learn, seemed strangely indifferent to police pay.

There used to be, however, another option for officers who chose not to take accommodation allowance - housing in a Met-owned property (for families or couples).

The Met was a substantial landlord, owning hundreds (if not thousands) of residential properties. When they sold them off (a fire sale from which the Met never recovered), a select few coppers made a packet when they were given first dibs on buying them. There was a brutalist block of police flats near Notting Hill nick called Mead House; a thirty second walk from Holland Park tube station, in one of London’s most desirable residential areas. I remember the very lovely Honor Blackman lived next door. A modest flat in the block now goes for north of 700K.

Then, for single officers, there were section houses. The words ‘section house’ just prompted a frisson of either deep affection or abject terror in a few of you, didn’t it? These were hostels for single officers, usually in urban areas. That is to say, part of the community and local economy.

I only ever lived in a section house for two weeks. It was called Douglas Webb, marooned in the edge-of-town wilderness near Heathrow. With all the charm of the motel in which Alan Partridge once languished, the much-vaunted ‘Animal House’ lifestyle of the archetypical section house was completely absent. The inmates were primarily divorced chief inspectors and coppers with an unnerving resemblance to Reg Hollis off ‘The Bill’. They would sit in the communal TV room, bickering over the remote control and eating takeaways. I sat there agog, wondering when Nurse Ratched would arrive with my meds.

There were no toga parties at ‘Dougie Webb.’

I ended up renting a groovy not-quite-central London flat with a mate from Hendon instead. By my early twenties I was well-versed in communal living. I’d been a cub scout. An air cadet. I’d been a keen army reservist, spending long summer months in Germany playing soldiers. I lived in a hall of residence at college. Tents, barracks and ‘Young Ones’ style house shares. Then, after six months living in one of Hendon’s tower blocks? Been there. Done that. No wonder section houses held little appeal, although I confess to moments of FOMO when hungover colleagues boasted of wild parties attended by local nurses.

Living over the shop - the old Tooting police station and section house

Why, then, was the Metropolitan Police a landlord? Why did it pay housing allowances? Why did it take such a paternalistic view of its officers for so long?

It was because (1) The Commissioner ORDERED us to live within 25 miles of Charing Cross and (2) the Met demanded we lived in accommodation ‘suitable for a police officer.’ It was paying your housing allowance, after all. An unintentional upshot of this was, partially, (3) a sense of community, belonging and loyalty to the organisation.

Stuff you can’t really quantify on a spreadsheet. So it had to go.

Officers were required to seek their chief superintendent’s permission to move anywhere, private or otherwise. You had to ask for a local collator’s check to make sure your potential neighbours weren’t drug dealers or axe-murderers. I remember applying to rent a flat in Shepherd’s Bush in the early 90s. The local collator called and said ‘don’t even bother, son’ because the neighbours were ‘known to police’. No wonder everyone moved to Ruislip or the Surrey borders.

More on this later, when I discuss long-time police botherer Kit Malthouse.

After my mate and I parted ways (he went to live with his girlfriend in a police flat) I had to find new digs - and I was damned if I was going back to Dougie Webb. Armed with a hard copy of ‘Loot’ newspaper (ah, the days before the Internet) I viewed a posh house-share in Fulham. Two Sloane-rangerish girls, of the sort you imagine preparing lasagne in an alpine ski chalet, invited me inside. Everything was going swimmingly, until I told them I was a policeman. “Oh,” said Annabel, looking at her friend. “That might be a tiny bit of a problem.”

“Yes,” said Melissa sweetly. “We do smoke a fair bit of weed at the weekend. Is that an issue?”

Yes it was. So that was the end of that.

This, ladies and gentlemen, is why the police used to concern itself with where coppers lived. Else officers without the young Pc Adler’s iron self-discipline might have found themselves plotted up with two attractive chalet maids, gone full-spectrum Cheech and Chong and failed a drugs test (I do occasionally kick myself for not trying to make it work). Section houses might have been, er, lively, but they helped avoid such earthly distractions. Shame Julian Bennett didn’t have one handy.

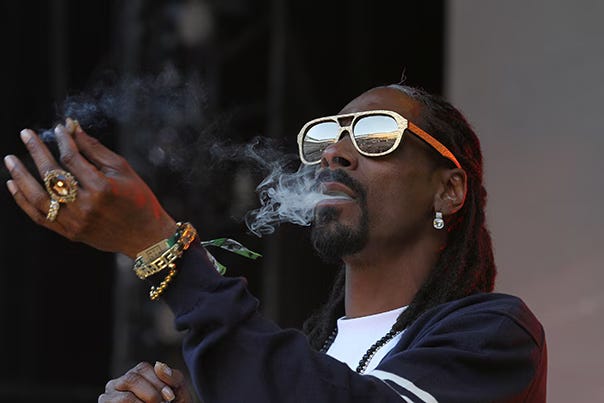

I love Snoop as much as the next man, but he’d be a problematic housemate for a copper. Fun fact; on one squad we had his voice programmed into our police car’s sat-nav

An aside; when they sold off police accommodation (and the 25-mile rule) and slashed housing allowances, you’ll be amazed to learn police officers began moving to affordable places ever-distant from London. Working on anticorruption, you’d think it would be easy to find out where targets (that is to say, cops) lived, right?

Wrong.

Police stations stopped keeping their ‘Book Ones’ up to date (which had all of the division’s up-to-date contact and address details). We’d spend precious time pinpointing where rogue officers lived if they were sofa-surfing, or living on-and-off with girlfriends and boyfriends etc. Or they’d be camped out in the arse-end of Somerset.

Then, when I moved to counterterrorism surveillance, officers would complain they’d have to travel in from Leicestershire or Southampton in the middle of the night on the hurry-up. I was conflicted - on the one hand I took their point, on the other why volunteer for a job where you knew you’d be expected to drive a hundred miles off the back of a phone call? The Met, corporately, had no answers. Except, of course, to occasionally bubble up officers to the Inland Revenue for the taxable benefit of taking a car home.

The sense of belonging was (rapidly) replaced by a sense of ‘tough shit’. That just as quickly became a two-way street between employer and the employed. Anecdotally, I think it got worse under Commissioners Blair and (especially) Hogan-Howe. H-H was particularly scathing about the Met supporting officers with accommodation issues. “I’m not a landlord”, he said, quite possibly gazing at himself in the mirror while admiring his new ceremonial uniform and peacock-feathered hat.

Things became even worse for frontline officers. They might have enjoyed subsidized public transport, but that didn’t mitigate the crippling cost of London rent (currently averaging over 2K pcm). Then they closed police canteens, so goodbye subsidized meals too. They suffered awful shift patterns which gave little or no thought to public transport running times (if the 60K a year drivers weren’t on strike again). There was a lack of car parking and, then, ULEZ. Officers were disciplined for sleeping in offices and changing rooms so they could make early turn. Then they were disciplined for being late for early turn. ‘Catch 22’ is, for the Met, an instruction manual rather than a satire on the stupidity of hierarchies. Tough shit.

Meanwhile, civil servants grumble about working three whole days a week in their comfy nine-to-five offices.

A Home Office official, busily working on ‘reforming’ police pay and conditions

I notice, though, very senior officers retained their police accommodation. Because of course they did. How else do you retain the unique talents of titans like, er, Sir Paul Stephenson? For many years the Met retained a Commissioner’s grace-and-favour apartment in Dolphin Square. Then they moved it to another fairly ritzy part of town. Bernie ‘I’m not a landlord’ H-H lived there occasionally.

Let them eat cake, eh?

Talking of the powers-that-be, you’ve been sitting on the edge of your seat, waiting for me to mention Kit Malthouse again, haven’t you?

No? Kit who?

Kit Malthouse has been involved in police policy-making for donkey’s years. He’s a conservative localist, I think it’s fair to say, who broadly favours private-sector solutions in policing. He worked as policing supremo for Boris Johnson when he was Mayor and is now a policing minister. At one point, when he was on Westminster Council, I remember him sort-of advocating private companies replacing beat policing functions (if I’m mistaken, Kit, get your people to talk to my people. I’ll happily issue a correction).

To be fair to Malthouse, I’m not suggesting he’s part of the oft-alleged ‘sell-it-all-to-G4S’ cabal many police officers think exists inside the Conservative Party. I reckon he’s more of a utilitarian (he trained as an accountant). Someone who views policing in spreadsheet terms. Someone who wants police officers to be like anyone else; a traffic warden or refuse collector. Just take your paltry municipal pay and be grateful.

In 2012, when austerity was really beginning to bite, Kit wrote this absolute gem, criticizing police for daring to live in areas where their kids might go to decent schools and not be robbed on their way home. There were rotting London slums to police - I demand you live in them too! It was, he suggested, part of a wider disconnect between the police and the policed (does this sound familiar? The wheels on the bus go round and round).

Kit knew full well the austerity-led Winsor pay apocalypse was coming. Did he write the article in bad faith - part of the wider Tory duffing-up of the police in the media to justify cuts - or was he simply clueless about the lives of coppers and how much they were paid? Or both, perhaps? I’ll let you decide. I mention it to demonstrate (a) the mindset of the people in charge and (b) how this has been the Blob’s direction of travel for years.

Kit, by the way, is now MP for a constituency in leafy Hampshire. He grew up in Liverpool and spent most of his career in London. You’d have thought he’d be aware people, you know, move around.

Yes, Kit, the barrios of Woking and Leatherhead are teeming with police officers with the temerity of not wanting their families to live in an overpriced slum

As usual, I will offer a few possible solutions. Here’s what I’d do if you put me in charge. I don’t even want or need a Job flat. And there’s no way you’ll see me wearing a hat with a peacock feather, either.

First of all, I’d liberate policing from the utter nonsense of national pay and conditions and let forces do their own thing.

Then I’d establish a comprehensive Met key worker scheme for subsidized housing (part-ownership). I’m actually quite dry when it comes to economics, but you can’t be a purist when cities are rotting and generational injustice has created people under 45 who think red-blooded socialism’s the answer to their woes (spoiler - it isn’t). These schemes are effective and fair. A city, if it wants top notch public services, needs to attract public servants who can afford to live in it. Now I think about it, it’s perfectly sensible market economics. I suppose Mr. Khan seems to be more interested in virtue-signalling and ULEZ but there you go. You get the police you deserve.

I would establish and maintain London accommodation for high-tempo and protracted operations. This might be a ‘Nightingale Hospital’ style portable solution. It might be former brownfield industrial sites converted into basic living quarters. It might be some sort of deal with the military, who own a fair bit of real estate. Let’s not go to Gravesend, it’s too far away. During large-scale public order events, state visits, summits, emergencies, terrorist outrages etc, the Met can say - if you can’t get home tonight, we’ve got your back.

I would reimplement section houses solely for new officers. Equalities legislation around age discrimination be damned or changed - our youngest, newest and potentially vulnerable officers deserve safe, affordable and welfare-orientated accommodation. This should be time-limited for, say, the first three years of service. It need not be free - simply fairly priced and affordable. Ask anyone working in mental health what difference this would make for the Generation ‘Z’ cohort currently being recruited. They’ve been hatched into a different world - there’s no point whining about it, let’s support them. They are our future. Let’s help them become resilient coppers.

Every shift pattern in the Met should pass a simple ‘can the troops actually make it into work on time?’ test. Every senior manager (superintendents and above) should work several sets of these shifts per month - travelling to work on public transport - to qualify for further promotion. Why? First of all, you lead by example. Secondly (you might want to sit down, boss), you aren’t that bloody special.

There will be a presumption anyone misusing or abusing these privileges - especially in a safeguarding or sexual context - will be immediately sacked. Tolerating idiots is why we can’t have nice things. It will stop forthwith under my benevolent, but occasionally harsh, reign.

Lastly, we often talk about Diversity in policing. Despite being a dinosaur, I’m on board with lots of the commonsense end of the business. A workforce living in and around a mix of communities at different times in their lives and careers is, to my mind, all part of a truly diverse workforce. A blended workforce. People who’ve lived in the city, in the suburbs and the spaces in-between. Malthouse-style diktats or Dixon of Dock Green community policing fantasies don’t cut it anymore. Those ships have sailed. Or sunk.

I’d also suggest if you really want diversity in a workforce, a sense of harmony, you need something else. Something we’ve lost. It’s tangible. It gives you something real. That might be a roof while you’re finding your feet. Help with finances. A boss who plans shifts you know you can make on time. A clean bed after fifteen hours behind a riot shield. An organisation that offers more than nice words, bean-bags and a multifaith prayer room. It doesn’t matter your religion, race or anything else - we all need a roof over our heads.

Ironically, given a diversity industry that venerates intersectionality, I’d also suggest it’s about embracing something bigger than yourself. It’s about rolling with the punches and acknowledging hardship and shared experience. It’s about being part of a team, with all the drama and excitement and (yes) problems that involves.

I call it belonging.

Have a good week, people. I’m still on sick parade, but at least my keyboard isn’t.

Dom

Regarding the suitability of an area for domiciling police officers on their occasional days off, I remember a case of one of the Sergeants on my relief, when I was a young and keen PC (I know, it's not the one you knew). Having been divorced for several years, he met and fell in love with a gorgeous lady, and decided to move in to her large Victorian mansion flat in one of the better parts of central London with her. Being aware of the rules, he made an official application to cohabit (the Job was slowly leaving Victorian morality behind by the late 1970s) The reply came back about 10 days later - refused. He showed me the 728 and his response, which was "I appreciate that there is a known prostitute living 5 doors away. I assume that you will be emptying Marylebone Section House, 3 doors away." He was thereafter allowed to live in an area cursed with ladies of the night.

Trenchard House … venue of legends. Stick a load of coppers with money to burn slap bang in the middle of Soho, what could possibly go wrong ?🤣🤷🏻♂️

I thought I’d live there for six months and save up a deposit for a flat. Actually moved out five years later when the job slung us out 🤪

Legendary parties, great people, great times. As someone once said, it’s like being at Uni but on £25k a year 🥳🎉🍻🍻🍻