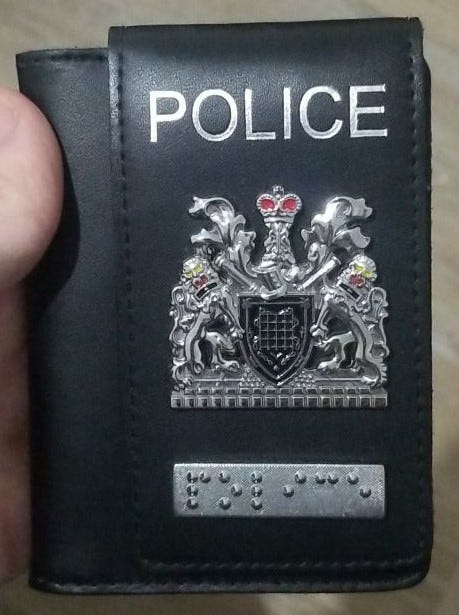

The warrant card; a cheap piece of leather and tin. Not a magic shield.

‘Showing Out’ is a term Metropolitan Police officers use for identifying themselves as coppers when off-duty. This means you’re obliged to show your warrant card. Your badge. Your brief.

Most experienced officers are wary of the practice. It means you’re putting yourself on duty without backup, comms or personal protective equipment. And you’re in Sainsbury’s, with the other half and your kids.

This sprang to mind when I saw this story about a Cambridgeshire officer falsely accused of sexual assault on a suspect after arresting him for drinking and driving. Luckily the officer was (a) in uniform and on duty and (b) wearing body-worn video. The suspect got a pitifully short prison sentence for attempting to pervert the course of justice (not to mention potentially destroying a police officer’s life).

I received a similar complaint making an off-duty arrest. In the days when there were no body-worn cameras.

So today’s piece is about the how, when and why coppers might find themselves in a situation where they show out. It’s also about something else common to policing - the official line concerning off-duty incidents versus the messy reality. What the Job preaches versus what the Job (and especially the public) expects are two quite different things.

I’m also going to mention a common off-duty scenario for late-service officers (like me) who found themselves in HQ-type roles - getting involved in arrests on public bloody transport.

Before I get started, though, a word about job-pissed police officers. These are coppers who love showing out, almost certainly due to some bizarre character defect. Like the off-duty Pc driving out of a multi-story who threatened to arrest me for not wearing my seatbelt. Karen Five-O produced her warrant card with glee - yes, it was the real thing. “There’s a teeny problem with your argument,” I replied sweetly. “The Road Traffic Act 1988 only applies to vehicles driven on roads maintained at public expense. This is a private carpark.”

I might have been wrong, but I won the 2015 Bullshitting World Cup in Las Vegas. The off-duty Pc glowered and drove away. Rule One of showing out is simple - don’t get involved in chickenshit incidents. Rule Two is also simple - know the law.

We even had a bloke at Hendon who was trying to stop people for speeding - in his private car - two weeks into training. These people walk among us. Although job-pissed officers seemed to have become rarer nowadays. Probably because showing out has become more dangerous.

When I was a policeman people would occasionally ask, “are you always on duty?” Obviously not, as I’d be paid for twenty-four hours a day and not eight. No, police regs meant officers are bound by police regulations 24/7. It also meant you could be recalled to duty at any time. You were also expected to intervene in incidents off-duty - although which incidents were never written down in black and white. Not that I minded. I’m all about discretion. It seemed fairly obvious to me what stuff you wouldn’t or couldn’t ignore.

It also meant, because of this obligation, you were always required to carry your warrant card.

It took me the best part of three years after I retired to get used to not carrying a warrant card. It becomes second nature. Incidentally, coppers come in two flavours when it comes to warrant cards; purists who use them strictly for ID purposes (like me), and those who use them as wallets or purses. You know who you are, with your Tesco club cards, crumpled tenners and pictures of your dogs. Sexist trigger warning ahoy - my female colleagues were often (but not always) the worst offenders.

This shameful meme, which might see me placed on a government hate incident register, equally applies to warrant card holders. This is my ‘lived experience’, so there;

If you are a female warrant card purist, I wholly apologise.

It’s the late 1990s, at a west London tube station. I was on my way for a drink after work with some college friends, wearing a suit, tie and a raincoat. I was also in my late twenties, nowhere near as fat as I am now and reasonably capable of looking after myself. As I walked out of the exit barriers, I saw a weaselly-looking bloke accost a middle-aged woman. “Gimme a cigarette,” he demanded.

“No, I’m sorry,” the woman replied apologetically. “I don’t smoke.”

“Then you’re a CUNT!” he hissed, lunging towards her and grabbing her shoulder.

You don’t really need to apply the ludicrously patronising National Decision-Model (which didn’t exist back then) to realise you’re showing out in these circumstances. I applied the old-school ‘what would I expect old Bill to do if that were my mum / missus / sister?’ rule. “Police,” I said (manfully), warrant card ready. I grabbed the bloke’s upper arm and pulled him away. “Leave her alone.”

At this point, the woman did what most witnesses do when you really need them and promptly fucked off.

Then it was all off at Haydock.

Weaselly-bloke was wiry, sweaty and stank of old weed and booze. Now, I was bigger but he was faster. Slippery, even. We began wrestling in the station entrance hall as he tried to scratch my face with sharp, grimy fingernails. I parried him, which was when he retched and gobbed a mouthful of phlegm in my face. I know, punching him in the grid would probably have been lawful, but it still wasn’t a great look. “You’re nicked,” I said pointlessly.

What was everyone else doing? For example, the station staff? Absolutely nothing. This is another common feature of the off-duty arrest, except nowadays drooling morons film you using their phones.

My girlfriend arrived to meet me. “He’s a policeman,” she said to one of the station staff, who’d found something compelling to read on his clipboard rather than notice two blokes scrapping in front of him. “Call for help!” Remember, very few of us had mobile phones back then.

Weasel and I continued to fight. He was quite the Angry Man, actually, even if our melee occasionally resembled the crap fight scene between Colin Firth and Hugh Grant in Bridget Jones’s Diary. Finally, I got him under a semblance of control, although he wouldn’t stop spitting. I pushed his head towards the wall, his claws still trying to rake me.

Someone dialled 999, the cavalry arriving with impressive speed. There’s nothing more reassuring than the old-school response to the ‘off-duty officer requires urgent assistance’ call. At least a dozen uniformed cops arrived, batons drawn, dragging Weasel away and bundling him into a station van.

Every time I hear a bleeding heart whining about police using spit hoods I get rather cross.

I went to the local police station with my prisoner. I gave the circumstances of arrest to the custody sergeant, who authorised detention. “Go and do your notes,” he said, “we’ll get something to clean the gob off your face, too.”

“Excuse me,” said Weasel.

“Yes?” said the custody sergeant.

“I’d like to see the duty officer please.”

“Why?”

“I’d like to make a complaint,” Weasel replied, a sly smile on his face.

“About what?”

“This officer,” he said, nodding at me. “He assaulted me, stole ten quid from my pocket and touched my cock.”

The custody sergeant raised an eyebrow. “You’re alleging assault, indecent assault and theft?”

“Yes.”

“You’ve never been nicked before, have you?”

I went and scrubbed my face with carbolic soap, hot water and a nail brush. Then I made my notes. Sitting in the canteen, the duty inspector came to see me. “Don’t suppose you arrest many people in special branch,” he said. “Are you okay?”

“I’m okay, Boss. I just want to get to the pub.”

“Your prisoner’s made a complaint.”

“What a load of bollocks,” I said with a sigh.

The inspector nodded. “Well, I’ll look into it. Have a good evening, okay? Just fax us a statement next time you’re on duty, we’ll take it from here.”

Here’s what happened next;

(1) I booked on for duty via telephone and was subsequently paid the grand total of four hours’ overtime for getting assaulted, spat on and receiving a potentially career-threatening complaint.

(2) I was two hours’ late getting to the pub.

(3) I tore the knee of a perfectly good pair of trousers.

(4) Weasel turned out to have a rich history of being a dickhead. I never heard about the complaint again. I hope Weasel fell into an industrial shredder.

(5) Weasel faced no consequences for making his bullshit allegations against me.

I thought little of the incident at the time. But looking back at it now? Given the risks, complaints, rubbish pay and complete lack of recognition, the public are lucky coppers show out at all. Yet they still do. Dammit, why can’t we employ more of the social-work adjacent types Ian Blair wanted for his New Model Met? We could all go home at 16.00 and not worry about it.

Luckily, policing continues to attract enough people who feel compelled to run towards situations others run away from. If that sounds maudlin or cheesy, then so be it. I don’t care.

The Job evolved and so did officer safety models. We entered a world of dynamic risk assessments and the withdrawal of the Commissioner’s vicarious liability in the event of accidents. Health and Safety legislation allowed for charges of corporate manslaughter. Police officers might be Crown Servants, but now they were employees too. Put simply, acts once deemed heroic were now treated as reckless and even worthy of misconduct proceedings (which actually happened - due to the case linked above - when an officer chased robbery suspects across rooftops against standing orders).

Much of what you and I might describe as bravery became, in effect, unlawful.

A more managerial, administrative way of doing business replaced an ad hoc, paternalistic approach. At local level, the Met used to ‘look after’ officers injured when going above and beyond the call of duty (who remembers ‘Superintendent’s Patrols?). Newer corporate HR, occupational health and legal processes seemed to work on the assumption injured officers were malingering (yes, some were, but the police does like to apply a broad brush - it saves money). I was medically retired due to an injury on duty. The processes I endured on my way out of the Job occasionally felt worse than the injuries I suffered in the first place.

Why is this relevant to a discussion on Showing Out?

I’d say it’s because policing is forced to skirt around a dilemma. On the one hand, it knows the public expects police officers to expose themselves to danger in emergencies, whether they’re on duty or not. On the other, it’s tied in legislative knots if anyone gets hurt. So policing, predictably, offers mealy-mouthed lawyer-ish guidance about off-duty conduct. Police officers have to do more than a ‘dynamic risk assessment’ when showing out. They have to do a ‘will I be looking for a new job in six months?’ assessment too.

Look, if you’re in a supermarket and a bloke pulls a knife on an infant, we all know what we expect a copper to do. And it isn’t offering him or herself as a passive witness after the event.

Which brings me onto trains, buses and the tube.

This racial incident took place in otherwise sleepy St Albans. Public transport environments can be dangerous, especially at night.

Most of my off-duty incidents, towards the end of my service, occurred commuting to and from work. Serving on big squads or specialist units, actually laying hands on suspects is fairly uncommon. How many detectives on a murder team? 40? They can’t all arrest Colonel Mustard in the library with a candlestick, can they?

Not so on the 16.30 from Paddington. Or, even worse, the vomit-comet last train from central London on a Friday night.

This became an issue because officers received free public transport on commuter trains a certain distance from London (although this, like every other perk, was eroded over the years). In return, not unreasonably, a condition of travel by the train companies was officers would intervene if there was aggro. Officers who, of course, weren’t allowed to carry PPE on their way to or from work (apart from, curiously, handcuffs).

On the one hand, we were being asked to intervene in incidents but without the tools to do so (tools the Job told us were mandatory to perform our role as constables, right?). Thus the mealy-mouthed tautology employed by police management about what you were expected to do if there was an incident. There was no escape either - you were expected to produce your warrant card to get on the train and to the onboard ticket inspectors.

It was the ultimate Show Out.

I was lucky. I lived in a fairly peaceful area (sorry, Kit Malthouse), but even then my commute was occasionally haunted by idiots. I’m a big bloke. And towards the end of my career I was also as mad as a badger (I am now only as mad as a wombat). I think it showed in my eyes on the occasions I confronted idiots on public transport. Here’s a flavour of a few;

There was the twentysomething playing very loud music on his phone and swearing to his mates who I kicked off a train at Richmond station. I mention it because I received a round of applause from the other passengers. Then there was the bloke having a shouty phone conversation in the quiet carriage on a train to Birmingham. Without showing out (there was no need, was there?), I asked him very politely if he minded keeping the noise down. Of course, he wanted a fight. So I showed out. The ticket guy arrived and (you’ll be shocked to hear) Mister Noisy had no ticket. He was ejected at a semirural station somewhere in the West Midlands and the stewards insisted on treating me to an endless supply of hot chocolate. Dammit, I just admitted to accepting a gratuity!

I even nicked a prolific London street gang member by accident. He was bunking an early morning train when the station staff detained him. The lad was quite charming and thought he could talk his way out of it. He had plenty of cash but criminals, for some reason, feel compelled to ignore simple rules like buying a ticket. He had no ID so I phoned work and got a PNC check on his details. How I laughed when it showed him wanted for non-payment of fines. A bench warrant too! The British Transport Police arrived and kindly took him straight to court.

At this point, I could discuss the wider societal benefits of encouraging police officers to show out when they’re off-duty. To support them. For the public to intervene on their behalf even, rather than making stupid TikTok videos. For forces to consider novel policies to allow officers to, if appropriate, carry PPE from work-to-home and vice versa. And for senior managers to give officers the benefit of the doubt when they put themselves on offer when they don’t really have (or want) to. You know, that whole goodwill thing?

But that would be silly. The Blob doesn’t want the bother and nor do the TikTok zombies; both are prisoners of the special little worlds they’ve created for themselves.

Thanks for reading and I’ll be back soon.

Dom

Why is it always the 'ratboys' who kick off? Some other points however:

You talk about HR, back in the 90's when there was one of the many MPS reorganizations, not sure if it was from 5 to 8 areas but they all blur together now, one of my colleagues came back from a meeting with a recently imported head of HR from the private sector who basically said 'why do you look after injured officers? Get rid of them'. And that is why there was a policy in the 90's that stated if you weren't fit for work you had to be medically retired. This lead to some interesting decisions when officers with minor medical complaints such as dodgy knees which could be fixed with a minor op and physio etc were binned. How much did that cost the MPS?

Does anyone remember one of the wonderful ideas from Policy Exchange dating back to 2011 which said that officers using public transport would be 'forced' to wear uniform to travel to and from work?

Getting involved off duty is rarely worth it, particularly in the current climate. Those of us who joined in the late 70's were strongly warned against it

I don’t know how you channel this stuff from years ago but it always gets me remembering. In 1988 I got off the last train to Willesden Tube and showed my brief to the only staff member, safely tucked away in her box. I walked down to the closed gates by mistake and she shouted out “Officer, these two haven’t paid”. I had no choice but to turn round and was pushed into the wall with a knife to my throat. “What are you going to do about it?” I was asked by one of the two. “Whatever you want” was my unimaginative but honest reply. The custody officer wasn’t troubled that night.