Does the Met have an appeasement problem?

Policing protest and extremism in an atomised Britain

The UK has long put proscribing Hizb ut-Tahrir into the ‘too difficult tray’

The Met’s in trouble. Again. This time for being too soft on the Islamist extremist group Hizb ut-Tahrir. When Hizb ut-Tahrir joined the solidarity with Palestine march last weekend, they chanted the solution to the issue of Gaza was ‘Jihad.’ When challenged on the decision not to make arrests, the Met said Jihad had ‘a number of meanings’ before airily concluding no offences had taken place.

Such sophistry is to be expected nowadays – and yes I know, in Islam, Jihad has a variety of meanings. Although I think it’s pretty obvious which version these guys meant, even if the Met’s specialists deemed otherwise. It also, I would argue, illustrates how discretion and fear are occasional bedfellows. Anyhow, the Home Secretary is very cross and has summoned senior officers for an interview without coffee. Three things immediately spring to mind;

The Met don’t seem to have a similar problem with acting on ‘non-criminal hate’ incidents against people holding contentious opinions over other, less incendiary issues than, er, terrorism. Nor do they seem to have issues with swooping on cells of bedsit-dwelling, extreme right-wing internet loons.

The Public Order Act 1986, which deals with behaviour deemed unduly aggressive or upsetting, uses the test of what a ‘a person of reasonable firmness’ might think (who, I think you’d agree, would know exactly what ‘Jihad’ was intended to mean in this context).

If you think an SO15 officer’s opinion of what Hizb ut-Tahrir’s words mean determines the arrest strategy for a major public order event, I’ve got a bridge to sell you. Hey, I could theoretically spin Hizb’s actions on Saturday into a S.1 offence of Riot. The definition being, ‘twelve or more people present together who used or threatened unlawful violence for a common purpose; and that the conduct of them was such as to cause a present person of reasonable firmness to fear for his/her personal safety.’

For the UK, as the repercussions from the current Israel-Hamas conflict illustrate, the Venn diagram of terrorism, extremism and public order often overlap. It’s a subject of enduring interest; as an ex-Special Branch officer I monitored dozens of demonstrations as an observer. I’ve attended public order planning meetings. I’ve sat in the control room at Scotland Yard as the duty SB guy, watching senior officers make on-the-fly decisions. Their job, by the way, isn’t easy. Protest’s a game which, for the Met, it’s nearly impossible to ‘win.’ For the record, if running public order events was a football match, in my day Lionel Messi would’ve been Commander Mick Messinger (if you know, you know). Mister Speed knew his stuff, too.

I digress. This Venn diagram is an absolute nightmare for senior officers, who generally speaking have little interest in politics (except those of the office variety). As I’ve written before, London’s a deeply complex, multicultural world city. There’s no hiding place from global geopolitics. I’ve also written about the Met’s tradition of softly-softly when it comes to public order policing.

This means the Met occasionally resembles an elderly grandparent trying to babysit a pack of unruly, bickering multinational teenagers. It doesn’t quite understand what they’re arguing about and frankly, doesn’t much care - all that matters is everyone calms down before something gets broken. Else there’ll be tears before bedtime, and nobody likes those.

Sadly, extremists don’t care about breaking things. For them, discontent is accelerant required for the bonfire they’re planning. Heavy-handed policing will do quite nicely (and the definition of ‘heavy-handed’ has been gamed by the Media and anti-Police left into ‘anything whatsoever apart from performing the Macarena’). I’ve witnessed many demonstrations where masked activists repeatedly goad coppers, praying one will snap and make an arrest. Then, it’s all off at Haydock for the ‘citizen journalists’ who only ever seem to photograph police use of force.

I’ve said it before, but it’s worth repeating; activists who bleat about British police brutality need to throw a traffic cone at a continental European gendarme. Those cuddly northern European social democracies have no problem with rolling out the water cannon, baton rounds and tear-gas when people misbehave. Don’t even get me started on the French, whose public order policing style sometimes makes me wince. However, if I’m being honest, it occasionally earns my grudging respect. If you can’t be loved, as Machiavelli astutely observed, being feared isn’t a bad substitute.

British police? Pussy cats by comparison.

And so, I ask, when does pragmatism - and the natural desire to avoid conflict - become appeasement? What’s more important? The King’s Peace on a rainy Saturday afternoon in central London, or allowing the knotweed of hatred to spread? Make no mistake, the likes of Hizb ut-Tahrir are not benign actors. It’s a tough question. Tougher than people on both sides of the argument tend to think.

London, 2011. The riots scar the memories of senior Met commanders. Risk-aversion is one of those scars

The complexity of the subject cannot be overstated. If the police get things wrong, they might provoke a riot. If an event goes off peacefully because a blind eye was turned, they send a message of appeasement. On Saturday, I would argue the Met achieved the first at the expense of the second. The problem is, as the IRA famously said, they only need to get lucky once. Police? They need to be lucky every time. Hizb ut-Tahrir won. Their message was spread. They will be emboldened.

On the other hand, nor do I think people realise how difficult arresting people is in crowds. I wonder how much the Met’s public order skills have atrophied. The mantras of community engagement and avoiding conflict seem to trump the hard but unavoidable truth that, occasionally, kinetic policing is necessary. Yes, I mean shield walls, baton charges, horses and snatch-squads. It means using lawful and reasonable force to demonstrate law-breaking will not be tolerated.

Part of the problem is logistics and personnel. At a demonstration, a police constable is a lost resource after making an arrest. Prisoners need to be ferried to a charging centre. They require processing, interviewing and access to lawyers. Procedures to expedite this stuff exists for larger demonstrations, but the fact is nicking someone takes a copper out of the game. They’re like bees with only one sting, one less precious crowd control asset. This means senior officers tend to make measured decisions on arrests for reasons of numbers as much as they do about the law. On Saturday, the police estimated there were 100,000 people out on the streets.

This is where, in the control room, discretion, common sense, moral bravery and experience come into their own. I think you might already appreciate the challenge - a cadre of senior coppers have ascended the ranks with a deficit in all four qualities. None of them want to blot their copy book by ‘provoking’ a riot or generating complaints of racism.

Then there’s the twisty maze of political considerations. The fact is few Met seniors will be overly troubled over the Home Secretary’s ire. They’ll reason she’ll be gone soon, and in any case they’re more concerned with what the Mayor thinks (at this point, it’s only fair to acknowledge Sadiq Khan’s unequivocal statement of support for London’s Jews). However, his Party (Labour) has strident pro-Palestinian supporters. It was, until recently, led by someone sympathetic to both Hamas and Hezbollah. London also has a sizeable British Muslim community, all of whom have a vote (and another reason why party politically-affiliated Police and Crime Commissioners were a bad idea). I’m acutely aware that relatively few British Muslims would countenance supporting Hamas - and that racists exist who’d make hay suggesting otherwise. I also appreciate many Muslims feel a natural empathy for their co-religionists abroad.

When emotions run high, waters are often muddied. A complex, multifaceted problem becomes, tragically, binary. That’s one argument, which I understand. Mine is it’s entirely possible to condemn Hamas’s actions for what they are - murder and terrorism, while separating them from wider issues of political legitimacy. I honestly don’t know how much traction my argument would have in a Met Gold Group right now.

And that, I think, is the ghost in the machine.

This highly-charged atmosphere complicates the operational independence of policing and ‘without fear or favour’ principles, steadily eroded by governments both Labour and Conservative. They have almost become a polite fiction, along with that old favourite ‘policing by consent’. It’s unsurprising politics is part of any senior police officer’s calculations on the mental decision log - the one they’ll never commit to paper.

Nor does public order policing exist in a vacuum; inevitably other societal issues shape the Met’s response. In a democracy, this is healthy. However, it’s also the space extremists will always seek to exploit, using arguments turning on freedom of speech and democratic rights (doubly ironic in Hizb ut-Tahrir’s case, given they advocate a hard line global theocracy).

I’m old to enough to remember when supporting terrorists was a social taboo. From the 1970s to early 1990s, London was occasionally shaken by Irish Republican terrorism. In south London, where I grew up, the visceral hatred for the Provos was palpable. Anyone expressing support for the IRA in a pub, for example, would invite a kicking. The precise politics of the situation was neither here nor there; the folk of the time had an admirably straightforward aversion to indiscriminate murder. Yes, there were a few Irish pubs where the ‘hat was passed around’ for terrorist funding. Yes, there was anti-Irish discrimination, stoked by extremists of the left and right. Our old friends the hard Left stood with the IRA, because of course they did. The Provisional IRA, it should be remembered, were neo-Marxists. I’m not sure what they are now (it was Gerry Adams who said, ‘they haven’t gone away, you know’).

The IRA’s Harrods bombing, in December 1983, killed six and injured 90

Nonetheless, people understood the majority of London’s Irish community (even those broadly supportive of a united Ireland) had little truck with the IRA. Nor was there any suggestion Irish areas like Kilburn or Ealing or Neasden would go up in flames if the British army shot and killed terrorists in Belfast or Armagh. Counterinsurgency, as TE Lawrence said, ‘is slow and messy, like eating soup with a knife.’ Note he was writing about the Middle East too. I’m not getting any further into the weeds of that argument now, but suffice it to say I think the IDF are well within their rights to destroy Hamas, as much as the British army did ambushing IRA men.

Now, a younger generation of Irish kids consider the IRA meme-worthy resistance heroes. A younger generation who are unable to see the wood for the trees. Something unambiguously wicked (Hamas’s calculated terrorist attack, specifically targeting women and children) has been reduced to a theoretical cog in the wider machine of anti-oppression and ‘decolonialisation.’ If there’s a hell, I hope the smug left-bank philosophers who invented this stuff are roasting in it.

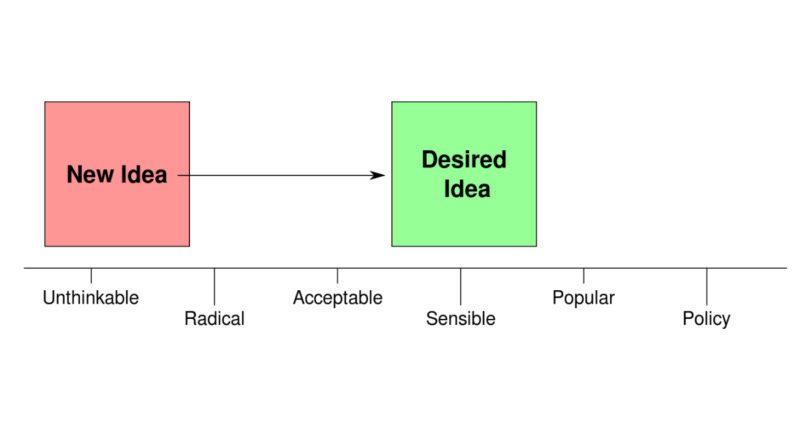

This attitudinal change is, I think, because the Overton Window shifted steadily leftwards. The ‘one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter’ brigade have triumphed. This represents a cultural victory for advocates of political violence, one where (pre-approved underdog) grievances can be nurtured into the casus belli for extremism, political violence and ultimately, terrorism. Identarian politics has also created a binary, topsy-turvy world of oppressors and the oppressed, one where the UK’s small and overwhelmingly peaceful Jewish community is somehow blameworthy.

The Overton Window. Terrorism is, I fear, becoming increasingly acceptable if committed in the name of certain causes or values

How should the police respond? Sadly, the track record isn’t good. I remember, in 1998, attending a Special Branch lecture on ‘Afghan veterans’ and the ideological threat returning fighters, radicalised by Jihad, posed to the UK. There were similar warnings over those who’d fought in Bosnia. Security Service officers despaired at the lack of concern shown by the Home Office. The French, famously, spent the 1990s warning us about our tolerance of radical Islamist groups. The UK demurred, it’s pro-Arabist foreign policy establishment arguing that showing neutrality to such groups would ensure they’d never blot their copybooks by misbehaving in Britain.

Look how that turned out.

The 7/7 bombers on their way to their targets. Did Britain’s tolerance of extreme Islamist ideologies contribute to a permissive environment for terrorism?

Add the subsequent era of globalisation and unprecedented levels of immigration? Some of which was the UK’s fault (Libya immediately springs to mind). Social atomisation was inevitable - not that anyone made serious efforts to mitigate it. The police, ever-sensitive to allegations of racism, drew in their horns. People noticed. After major terrorist incidents, for example, police were accused of prioritising the reassurance of Muslim communities. Was there, they asked, shades of virtue-signalling at a time when most people were thinking about all of the victims (including Muslims)?

For example, after 7/7, I remember Brian Paddick being duffed up in the papers for allegedly being overly preoccupied with this issue. To be fair to Brian (whose heart was in the right place, but also in the vanguard of politically-correct coppering) wasn’t responsible for counterterrorism strategy - he was charged with keeping the Queen’s Peace. People seem to have forgotten the racially-charged public disorder in the northwest of England in 2001. Brian Paddick hadn’t, and nor had the government of the day. They looked across the Channel, to France, fearing the creation of Banlieue full of weaponised, angry youths. Spinning these plates was all part of the delicate equation senior officers were being asked to perform.

I assure you, from personal experience, preserving ‘social cohesion’ and preventing disorder on the streets is a fundamental police and government concern after a terrorist attack. If only preventing terrorism was given similar priority. The UK’s PREVENT strategy melted into a fluffy, morally-conflicted mess when it came to combatting extremism. For example, nobody can look at the disgraceful sequence of events leading to the Manchester Arena attacks and say otherwise.

I will reiterate: no element of policing exists in a vacuum; police failures are often indicative of societal failure. A mirror. The failure to properly manage extremism is just one example, especially when ‘extremism’ has become a chimera, one over which people no longer agree. Home Secretaries can stamp their feet, but it’s politicians who shape the space in which police operate. And the current party has notionally been in charge for the last thirteen years.

At this point, commentators of a conservative (small or big ‘C’) persuasion might rail against the iniquities of political-correctness or civil service intransigence or police timidity. That might even be valid to a greater or lesser extent. But if politicians simply watch the Overton Window rather than try to frame it? At this point, Robert Conquest’s second iron law of politics comes into play. “Any organization not explicitly and constitutionally right-wing will sooner or later become left-wing.”

Thirteen years. They had thirteen years. And they absolutely blew it. Maybe a long period of time on the naughty step of opposition will help the Tories reflect on their parsimony and neglect. I’m not expecting much from the other lot, either.

Go on then, Dom, a person with no command experience - what would you do about the Hizb ut-Tahrir issue? An entirely fair question. Okay, here we go (for what it’s worth). Hey, I did spend a few years in the presence of legends like Mick Messinger.

In the days before the demonstration last Saturday, the GOLD commander should have been provided with a risk assessment. This would advise him or her of the likeliness of isolated incidences of provocation by extremist groups (I know because I used to write them). Furthermore, they’d be warned such extremists sought to deliberately undermine community cohesion, especially towards the Jewish community (excuse my sterile prose, this is how this stuff is written).

The operational order would continue:

The Met’s legal department has provided a comprehensive briefing note for SILVER and BRONZE commanders, to communicate to officers the legal position on our arrest strategy. Arrests made in good faith will be fully supported by the MPS.

Prior to the event, officers will make contact with members of Hizb ut-Tahrir and other appropriately identified groups to inform them their behaviour will be carefully monitored.

Incidences of language or behaviour contrary to Common Law, the Public Order Act and / or Terrorism legislation will not be tolerated. We have communicated this to the organisers of the march and are working closely with them to ensure public safety. Proportionality however requires us to be mindful of the circumstances of arrests (Dom note - I’m referring to singing ‘From the River to the Sea’ which, although loaded with meaning, has been tolerated to the point of precedent - toothpaste is difficult to put back into the tube. It would also involve arresting several thousand people, potentially radicalising some of them. Choose your battles wisely).

A dedicated arrest team of level one public-order trained officers, forward intelligence teams and evidence-gatherers, supported by SO15 detectives, will identify, arrest and investigate any offences committed by groups such as Hizb ut-Tahrir. They will be policed fairly but robustly. Prisoners will be conveyed to Charing Cross police station, where custody space has been reserved.

Such action will reassure the wider community that the Metropolitan Police Service takes their concerns seriously, and that extremist groups are unable to exploit peaceful protest to spread violent messages contrary to the law.

Not difficult, is it? And if it kicks off? You draw a line in the sand. Then you stand by it. It’s called policing, it’s called the King’s Peace and it’s called the law. We ignore it at our peril, because at the moment? When we go eye to eye with those who seek to do us harm, they know we’ll blink first.

I was intrigued by the police crowd estimate of ´100,000’. I thought police crowd estimates were not published any more. Has there been a change in policy?

Mick Messenger.... halcyon days indeed. Some of the quotes I remember from that time, usually delivered before a particularly contentious public order event, 'this is eminently doable' and 'panic slowly'. Mr. Messenger had, if we are using footballing terms an ability to put his foot on the ball and slow the game down. Like the best footballers he always seemed to be several moves ahead of the game. Unlike today we did not have to deal with everyone walking round with a hand-held device that could stream HD pictures instantly around the world, neither did we deal with 24/7 rolling news and batshit crazy commentators to the same extent that the police have to deal with now.

The media and politicians can't ( or more likely won't) understand the complexities behind public order policing. I had about 5 years in when the Scarman Report came out. One of the findings was that keeping the peace is not the same as enforcing the law. You wouldn't get any thanks if you sparked large scale public disorder attempting an arrest for a minor summary only offence.

Charge centres, support staff and just resourcing the event as well the problem of dealing with various iconic locations are part of the 'permanently operating factors' the old Soviet Stavka used to refer to. No matter how much you wish them away you have to deal with them.

Finally we have to deal with the extremely hypocritical British attitude towards the use of force by police. Wear public order kit and one sector of the public will complain that it's too oppressive whilst the other side will complain that not enough force was used, mind you both XLW and XRW will see a simple push as outrageous and proof that the UK police are the most violent in Europe. ( Laughs in CRS and wonders how British demonstrators would cope with the French propensity to go ugly early).

I've got to come back to my idea of fantasy public order - 'Today you will be policed by the German Bereitschaft Polizei who are operating under their rules of engagement and using their own equipment, next week the Royal Marechaussee are coming over from the Netherlands. They have the admirable motto of 'als hop erop aan komt' or 'when it comes down to it'. None of that fancy Greek or Latin for them. As they're Dutch they're big boys and girls and you will no doubt be pleased to know that they water-cannoned 2,400 Dutch environmental protesters off the road in September as well as using water cannon, mounted branch and tear gas on football fans after the Ajax-Feyenoord match. Enjoy'.

On a serious note I do not envy any met senior officer, they have to deal with Suella Braverman who is a genuine dimbulb and Sadiq Khan who is a world class weasel. The job gets closer to being impossible to perform every day.