1848 and All That

Keeping the King's Peace

Old-school public order – muskets, bayonets and no ‘legal observers’. ‘On the barricades on the Rue Soufflot, June 1848’, by Horace Vernet

Two things happened last week - both linked to the maintenance of the King’s Peace.

The first was when the perfidious Met were (allegedly) underhand in their dealings with anti-Monarchy protestors at King Charles’s Coronation. Too harsh! came the cries from the peanut gallery. Then, a Met officer politely asked Extinction Rebellion (XR) protestors not to walk slowly in the middle of the road. They refused and carried on anyway. “That’s a shame,” the officer mused. Too soft! came the cries from another peanut gallery.

The second (Halley’s comet-like) occurrence was a UK newspaper publishing a well-informed and even-handed article about public order policing. I’d like to say bravo to Abigail Buchanan and Lucy Foster of The Daily Telegraph. I’m perfectly happy putting the boot into journalists, so it’s only fair to point out when they do stuff well.

So this week, I’m writing about the maddening complexity of ‘Public Order Policing’, i.e. how Police manage crowds, protests and disorder. I’ll throw in some history and a little personal perspective too - I worked on public order intelligence and event planning (which sometimes involved attending demonstrations as a ‘spotter’). I’ll be discussing;

How policing protests to the satisfaction of all is virtually impossible

Legitimate protest activity has to be fairly facilitated… and why I don’t want to live in a society where it isn’t

Police decision-making, including the good, the bad and the ugly

How the general - non-demonstrating - public are poorly served when it comes to policing large events

Why the requirements of the UK legal system lead to inconsistent operational outcomes

Where to buy the best pint of London Pride while monitoring a demonstration in Central London

Les Stormtroopers: French police are renowned for violence - most people in the UK don’t realise the continental public order policing tradition is fundamentally paramilitary

Compared to our continental neighbours, Britain hasn’t really ‘done’ revolution. Some might try to persuade you otherwise, citing the Chartists, Gordon Riots, Peterloo Massacre, General Strike… all the way to urban unrest in the 1980s, Miner’s Strike, the Poll Tax fisticuffs of 1990 and the 2011 retail riots.

Yes, the UK has a rich tradition of protest. However, compared to our neighbours, we’re genuinely little league. We’ve never changed government as the consequence of a popular uprising - unless you count the English Civil War (which I don’t - Parliament versus Crown is a totally different kettle of fish). We’ve never deployed our army against British citizens - not in living memory, anyway. We indulge in pearl-clutching at the sort of paramilitary tactics common in countries we think of as liberal - such as the Netherlands and Germany - who think little of deploying tear gas and water cannon.

For UK policing, a key date in public order policing is 1968. Student uprisings swept the West, spawning a generation of tiresomely portentous (and invariably bourgeois) political thinkers and activists. The anti-Vietnam war protests outside the US embassy on Grosvenor Square were especially (and unusually) violent. Angry, well-organised protests prompted a complete rethink of how British police forces handled public order.

Grosvenor Square, 1968. © David Hurn / Magnum Photos

Which brings me to 1848, a key moment in understanding why British and Continental approaches to protest diverge. From 1804, many European countries used Napoleonic Code. It should also be remembered Napoleon was a child of the 1789 French revolution - he was in no hurry to suffer the same fate as Louis XVI. Viewing internal dissent as an existential threat, he was very much in favour of putting down protests using the army.

By 1848? Europe’s burgeoning middle-classes were seething with dissatisfaction at the ruling classes and the post-Napoleonic political settlement. The Congress of Vienna in 1815 might be viewed as a sort of nineteenth-century Davos, where Europe’s top dogs divvied up the future to their advantage. In an era of radicals, gendarmeries and secret police, 1848 led to revolutions and uprisings across the continent. Although largely unsuccessful in bringing about regime change, Europe’s elites were put on notice.

Did they choose liberalisation or repression? Well a little of the first, and a big old dose of the second.

By 1870, Napoleon III famously instructed Haussmann to design Parisian boulevards with cavalry in mind, lest they need to put down any uppity locals (I once heard the University of Kent, rebuilt shortly after 1968, was designed specifically with riot-prevention in mind).

There were no such uprisings in early Victorian Britain - despite Chartists marching in London and the potato famine in Ireland. I’m not suggesting any implied virtue here - British public order policing was pioneered in Empire, both near and far. Thus the legacies of Amritsar and the Black and Tans. Our ‘gendarmes’ policed Palestine, Hong Kong, Africa and Singapore, leaving Britain to the relatively benign care of watch committees, sheriffs and (eventually) constabularies. If there was a dust-up, we’d send in the Yeomanry - auxiliary soldiers on horseback. We could be proper bastards, no two ways about it. Just not on our doorstep, if you don’t mind.

In short? Domestic continental policing developed through a statute law system (rigid and non-negotiable) enforced by paramilitaries. Mainland British policing developed through a common law system (flexible, given to compromise), enforced via a civilianised, policing-by-consent model.

And never the twain shall meet, although New Labour had a bloody good try with the Human Rights Act (etc). The cat’s cradle of contradictory law we’re suffering now is in no small part down to Tony and Cherie (who is a too-often unrecognised legal heavyweight) Blair’s ‘lawfare’ between 1997 and 2008. Too much 1990s law concerned itself, in my opinion, in trying to shoehorn European-style legislation into a common law model (q.v. RIPA).

I’d argue understanding this stuff is crucial when understanding how British police approach protest - either good, bad or indifferently. And, of course, none of this is referenced in any police training material I’ve ever seen.

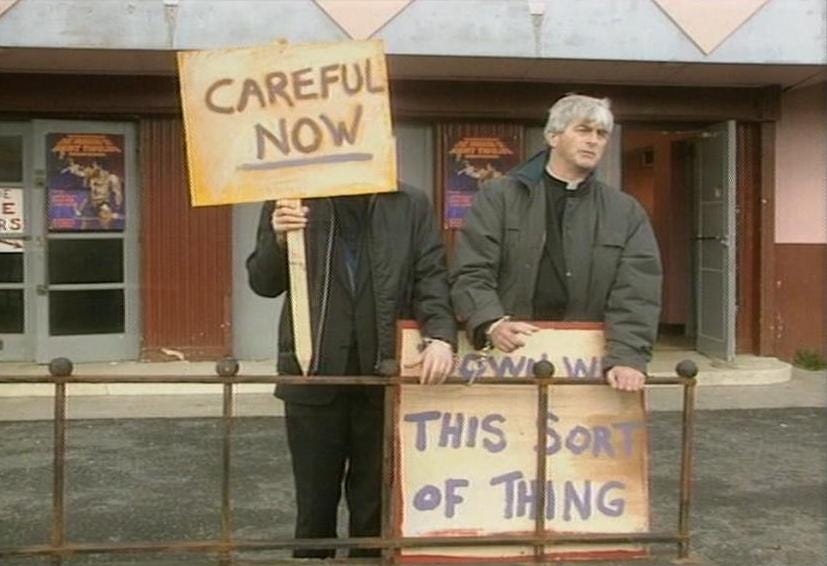

Making decisions at a demo - “let’s have a little think about this first, shall we?” We all know the feeling, mate

Which brings me to the Law. No, I’m not going to list the dog’s dinner of English and Welsh public order legislation (life’s too short). The fact of the matter is this; our system relies on (1) policing by consent, (2) common law (3) proportionality, (4) the principle that protest should be facilitated and (5) that each case turns on its own merits.

Put simply, we don’t have one-size-fits-all public order legislation.

Police commanders are expected to look at law and procedure in the round, a bit like a golfer identifying the best club to drive a ball down the third hole of a tricky links course in a crosswind. And, of course, some commanders are better at this than others. How, for example, do you think this happened?

April 2023 - when public order commanders go bad; uniform police on foot and bicycles end up chasing the Prime Minister’s protection team along Whitehall during a demonstration. Ooops!

Then there’s the cat-and-mouse nature of protest groups. To be fair, most organisers act in good faith when engaging with police. This is why allegations the Met were double-dealing when negotiating with anti-Monarchist group Republic are so damaging. People are compelled by law to inform police of demonstrations - agreements made should be honoured by both sides.

In this case, I can imagine the Met deciding to ‘take a punt’ with a hastily-introduced piece of law to test legislation in the courts. It’s a win-win (in the short term), because the Met had an incident-free Coronation (and if you don’t think politicians didn’t have a word in Mark Rowley’s ear, then I’ve got a timeshare in Bakhmut to sell you). If the Met get their wrists slapped in court? Small beer, really. Hey, they might even get a stated case out of it. The lawyers will be happy, I’m sure.

My problem is this: it appears Republic engaged with the Met in good faith. If I’m honest? I can live with people who refuse to engage with police getting kettled, messed around and generally inconvenienced - usually because they’re a pain in the arse to the majority who simply want to live their lives and go about their lawful business.

But groups like Republic who played the game? That’s completely different. As it stands, it looks like allegations they were planning any disruption to the Coronation procession were incorrect. Until that’s proved otherwise, it looks like the Met were sharp on this one. Trust - hard won, easily lost. A cliché because it’s true.

By the way, I’m a gentle sort-of monarchist with no axe to grind with the Royal family. On the other hand, I find Republic (from what I’ve seen of them) to be a po-faced bunch of spoilsports. It’s just when you start undermining the rights of people with who you disagree… you’ve no leg to stand on when the authorities begin undermining you. QED, on this one, I’m with Republic.

The Red Lion - back in the day, t’was an excellent place for watching demonstrations. An excellent pint of London Pride was a bonus

An aside - My old squad were occasionally used as plainclothes ‘spotters’ on demonstrations, giving us a welcome day out of our Scotland Yard office. I’d call in the location of activists most likely to cause trouble to a FIT team (Forward Intelligence Team) for further monitoring. We’d be issued what we called a ‘bingo card’ of photos of people who’d been arrested at previous demos.

One of my favourite games duties was guessing the size of crowds. Along with our colleagues from the-then CO11 public order branch, we were asked to provide the official police estimate. Contrary to the commonly-held opinion of protest groups, we tried our best (unlike many groups who’d big up their numbers). I would sit on Whitehall (occasionally taking cover in an ‘observation post’ such as the Red Lion) counting ranks of demonstrators and multiplying them by the approximate number of heads in each. Then I’d call one of the (uniformed) CO11 photographers to compare notes. We’d split the difference, although after five pints of London Pride I might have double-counted.

We ended up in some lairy situations while ‘spotting’, but the subject probably deserves a post of its own. Another time, perhaps.

“An SWP spokesperson claimed three thousand people attended their latest demonstration…”

Nowadays, the law’s complicated by what I consider to be a bizarre ruling by the Supreme Court, giving due regard to Art. 10 & 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights. To whit, DPP v Ziegler (and others) (2021) turned on an appeal concerning arrests made at an arms fair in 2017. The case is a feather in the cap for Matrix Chambers (deeply connected to - of course - Cherie Blair KC). It’s also the sort of ivory tower ruling that only makes sense after a long lunch in chambers, M’lud.

This means - “In an important judgment, the UK Supreme Court (UKSC) has ruled that deliberately obstructive protest on the highway retains the protection of Articles 10 and 11. Even when a protest blocks the passage of others, the assessment of proportionality remains a fact-specific and evidence-based assessment.”

In English?

The police are now required to carefully assess what sort of disruption a protest causes before deciding on its legality and action to be taken. Given our policing model and use of discretion, I’d suggest every constable be allowed to look at a straightforward piece of highway obstruction by XR and apply a ‘Ziegler Test’ along the lines of, “look matey, I appreciate you think stopping Mrs. Miggins from getting to Tesco is helping save the planet from Armageddon, but let’s face it - you ain’t. Now move off the the King’s Highway before you get nicked. Okay?”

We used to call this ‘reading someone their fortune.’

No, that would be too simple. Modern policing, configured as it is to suit the whims of the commentariat, noisy pressure groups and paid-by-the-hour legal clerisy requires special decision-making models, committees and processes. The sort of inelegant bureaucracy that one might expect to find in a Soviet- era Agricultural ministry.

Which is why police officers have to traipse around with the slow-walking solipsists of Extinction Rebellion, looking utterly ineffectual in the process. In the meanwhile, a bunch of bureaucrats at Scotland Yard and Transport for London try to model disruption for proportionality reasons (clue - slowing down an ambulance - or even the possibility - is bloody disruptive). And so the machine cranks and whirrs.

Unless, of course…

(1) You’ve just been bashed up in Parliament by a very, very rude Lee Anderson MP for not getting a grip, or;

(2) There’s a Coronation.

Then, magically, stuff happens! Arrests are made. Collars are felt. Areas are cleared. Maybe that’s the price we pay for our public order policing model - a classic slice of British fudge.

I suppose it’s better than having a baton-gun, stun-bomb armed gendarmerie - who I suspect seldom find themselves troubled by the minutiae of Articles 10 & 11 of the ECHR.

I find baffling and chilling is the ignorance of Ziegler among those including so-called journalists and politicians who regularly lay into policing and the Met. Equally is in the inability, seemingly intentional, of Parliament to do anything about it. Therefore I assume Parliament supports the judgement. Or is too weak, stupid, pathetic,bovine and useless to get off its collective arse and do something. I've grown to expect bizarre judgments from judges after three decades of policing. They seem to revel in being awkward, perhaps its the wigs. As for Parliament, I am increasingly scornful, contemptuous and I tolerant of it. A pox upon them all.

Does anyone else reckon that both left and right wing journalists were absolutely aroused at the prospects for the Coronation? For the right had the anti monarchists succeeded in disrupting the occasion there would have been endless articles about 'woke' policing whilst the left to an extent can go on about living in an authoritarian regime. As you say public order policing is a no win game for the police, they're either too hard, too soft or on some occasions are both.

Prospects for the future? The anti-monarchists will come again as will Just Stop Oil and ER. The police, and the Met in particular will continue to be criticised no matter what they do. I occasionally speak with people who either cannot or are unable to comprehend why demonstrators are not bludgeoned out the way like they are abroad does not happen here.

Finally how about a bit of fantasy public order policing? We invite over dedicated public order units from our European colleagues on a regular basis and let them deal with public order/protest as they would in their own countries. Just for the LOLS as I believe the young people say.