A McKinsey consultant makes a startling discovery

Today’s article was prompted by someone in the consultancy business (a chap called Roger Martin) tagging me into a LinkedIn post, asking my thoughts on a piece he’d written about transforming police culture. It was good to be asked and I appreciated the opportunity. Roger’s piece is thoughtful and optimistic.

Yet my reply (you’ll be astonished to learn) was pessimistic, negative and world-weary. Don’t get me wrong – I think it’s great that people outside of policing are interested in how the service works. It’s even better when they want to help. Sadly, though, consultants seem to pitch their ideas - through no fault of their own - at the wrong level. Police culture must seem scary and impenetrable to outsiders, quite possibly for good reason.

You see, it strikes me as ironic to aim change programs at the Met’s Management Board; haven’t command and control management models been (correctly, in my view) identified as suboptimal for UK policing?

QED, it must follow you can’t really implement meaningful change via a command and control model.

I might be wrong - I’m not a management or change consultant. I am, however, a battle-scarred victim / survivor of multiple change programs in the UK’s largest and most troubled police service. Few of them improved anything. They usually felt like a tactical withdrawal under a barrage of criticism, budget-cuts or naked careerism. Or, occasionally, all three.

To quote Game of Thrones’ Littlefinger: ‘Chaos isn’t a pit. Chaos is a ladder’.

I’ll set out my stall straight away – my police experience has made me a staunch advocate of localism, not command and control. In military terms, I would favour Auftragstaktik (German for mission command - the Prussian military invented the concept) every time. The opposite is detailed command.

Put simply, mission command allows local leaders, usually the most situationally aware, to determine how to achieve a given objective. Detailed command – which you’ll be unsurprised to learn is usually preferred by police – involves senior leaders dictating exactly how their subordinates should achieve an objective. This can result in micromanagement (until something goes wrong, whereupon the bosses retreat to their decision logs for some, er… retrospection).

There are occasions where one approach is preferable to the other, with a sweet spot between latitude and control. This requires the right sort of people. And when your workforce is overwhelmingly young and inexperienced, that’s a big ask. This also creates a self-replicating problem - when your people are deskilled in decision-making, how do you create successful decisionmakers?

Incidentally, if you’re interested in this stuff, you might like the concept of the ‘Strategic Corporal,’ which concerns the importance of coalface decisions on organisational objectives. To my mind, police change programmes should support the ‘Strategic Constable,’ not the ‘Tactical Assistant Commissioner.’

Silly hats. Horses. Swords. Lord Hogan Howe, the poster boy for command and control

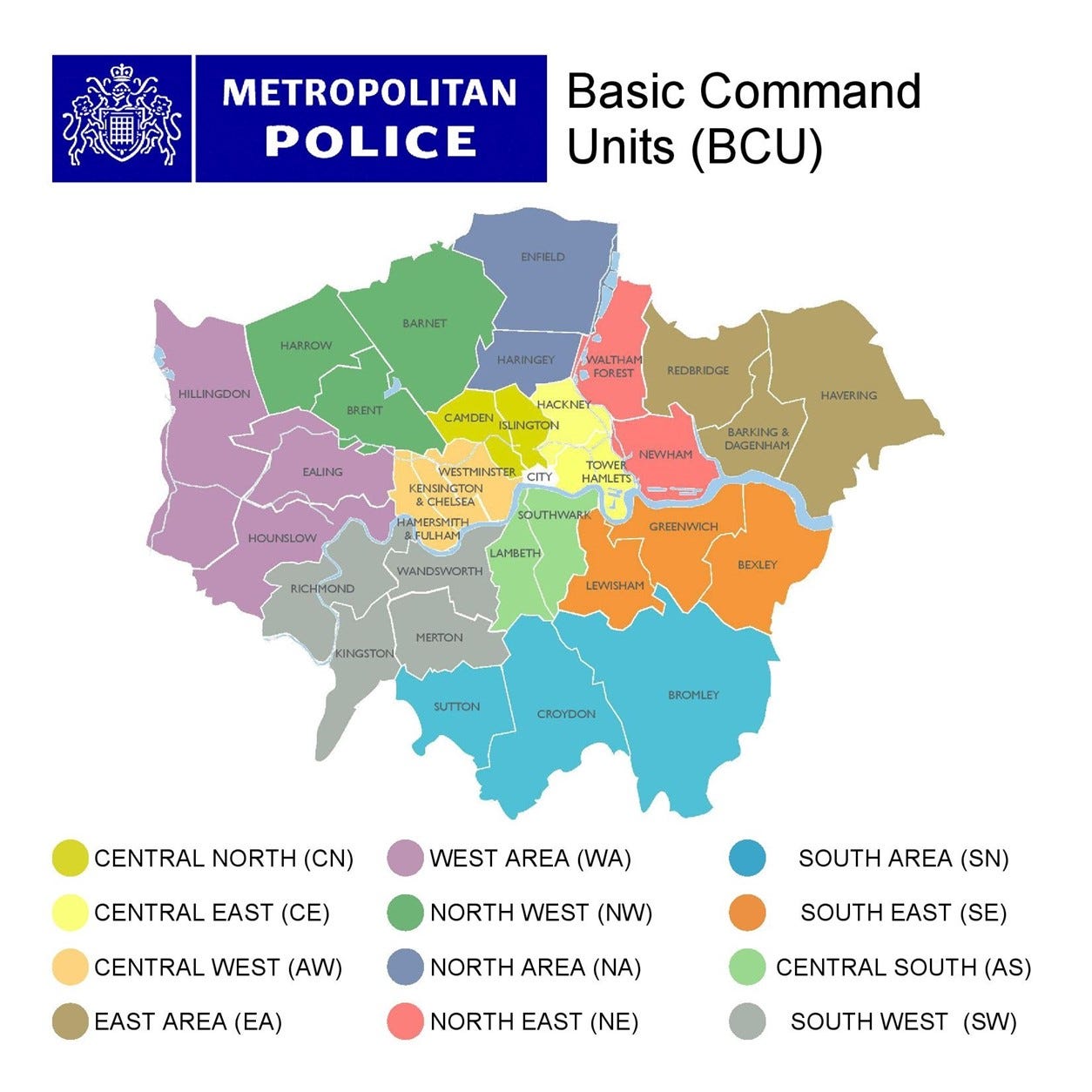

In any case, an element of control freakery is baked into police culture - even more so in our occasionally moronic era of social media. Control freakery can lead to operational fuck-ups (the Stockwell tragedy springs to mind) as well as organisational fuck-ups (the Met’s move to Basic Command Units is an obvious example).

My most effective policing was under managers who simply set parameters then let us get on with the job. They’d keep an eye on us, but knew when to loosen the leash. Or take it off completely. And, most importantly, when to shield us from the never-ending torrent of bullshit emanating from Scotland Yard. Such managers are rare, invariably hitting Adler’s Glass Ceiling (the mysterious barrier preventing sensible people achieving high rank) at superintendent or chief superintendent level.

Denial is another problem. When it comes to change, very senior officers are required to convince themselves they’ve radically turned the dial. In reality, though, all they’ve done is:

(a) Held a series of self-congratulatory seminars and / or focus groups. My favourite comment from a focus group was made by an especially cynical constable. When asked about the reason for his candour, the PC replied ‘what have the Commissioner and I got in common? We’ve both reached the rank we’re retiring at.’

(b) Spent a fortune on management consultants, who were of course briefed by the brass on the preferred ‘direction of travel’ on day one

(c) Fought a bloody series of skirmishes to punish rival groups of officers, burnish their promotion prospects and expand their empires

(d) Order their long-suffering middle-managers to implement change via what, in the Met, we used to call the ‘Nike’ model (Just Do It, changed in Metspeak to Just Fucking Do It)

(e) Plastered finger-wagging posters over the few remaining (and crumbling) police buildings

(f) Waged a passive-aggressive carpet bombing campaign via intranet and email

(g) Spent even more money on a hilariously patronising distance learning package, destined to be clicked through without reading by knackered officers on night duty

(h) Set the scene for another round of utter failure, necessitating a new change process (trebles all round!)

Progress is declared by a very senior officer, usually in a reflective and self-flagellating Guardian interview. This bullshit is what Russians call Vranyo, the doublespeak one finds in repressive regimes; it’s common knowledge everyone’s talking bollocks, but people are too scared to admit it. If they do, they’ll be labelled ‘unhelpful’ and shunted to the police version of Siberia (a BCU).

I remember one ‘anonymous’ feedback process where local management were able to identify officers who gave critical replies (the data used length of service metrics which could be used to calculate who gave negative feedback). The names of those officers were, as they say in the Job, ‘seen and noted’. Unsurprisingly, hardly anyone filled out subsequent questionnaires.

Police constables critical of local management report for their new posting

Another recurring problem is the complexity and scope of change programmes. Why? I could save McKinsey a fortune off the top of my head. For example, most coppers would be grateful for (1) a canteen, (2) a shift pattern that wasn’t designed by Torquemada and (3) somewhere to park their cars. Yes, cars, Mayor Khan. Police officers work antisocial hours, even if you don’t.

To little old me, easily implemented changes are quick wins, improving morale, performance and ultimately the culture. Happy people are less likely, in my experience, to be toxic dickheads. Sadly, no thrusting chief superintendent ever made it to PNAC by being an advocate for fried breakfasts, work-life balance and carparks.

You’d often see the following quote pinned on the walls of many inspectors offices:

We trained hard . . . but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams we would be reorganized. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing; and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency, and demoralization - Gaius Petronius Arbiter – 210 BC

Sadly, Gaius Petronius Arbiter never said this. Maybe it was written by his put-upon staff officer after the 2nd Legion was folded into the 3rd after another unfortunate dust-up in a German forest.

Then there’s the often-cited resistance to change, whereby pesky rank-and-file officers are painted as defensive stuck-in-muds. I find this ironic, given policing is an occupation predicated on uncertainty. Coppers are presented with dramatic changes of circumstances every day. For starters, the average constable has no idea what time his or her shift will end – they routinely have to be kept on duty for hours. Other exciting variables might include; will I be punched or spat on today? Will I have to tell someone their husband committed suicide? Will I get a complaint, and if I do will it take a year to be resolved? What new laws and procedures will I be ordered to learn this week, replacing the ones introduced the week before? Will I need a degree next year or not?

No, change isn’t a problem for most police officers. Shitty change, implemented by promotion-hungry halfwits, is.

What passes for a canteen in the modern police service. And then, if they do eat in public, people want to know why they aren’t working

My next point is London-centric – I was a Met copper after all. Mind you, to all the county chief constables enjoying a moment of schadenfreude at the Met’s woes, I’d say this: take a good, hard look at yourselves. Many of the issues recently identified by Baroness Casey apply to all UK police forces. How do I know? I was part of a specialist anticorruption team. We worked collaboratively with Professional Standards Departments across the UK - I’ve probably helped investigate as many county cops as I have London officers. The problems are startling similar in forces large and small.

Anyway, to London. Is the Met too big? I don’t think so. You see, most native Londoners will tell you London isn’t really a coherent city. It’s a mess of interlinked villages and towns, many of which don’t even map to current borough boundaries, which were introduced in 1965. For me, the problem isn’t London – or the Met – being too big. It’s about the structures trying to control everything being too small.

Does that mean more management? No. Please, for the love of God, no!

What it does mean, though, is more local control of operations. It means trusting local commanders and their officers. It means creating a service where officers are given meaningful career development at local level (which also means they’re less likely to leave for a specialist unit as soon as they can). It also means (fasten your seatbelts, chief officers) police borough ‘a’ might police – and look – radically different from police borough ‘b’. The myth of consistency of service is just that - a myth. Consistency and quality comes from people, not diktat.

Each Met BCU is larger in terms of staff and population density than the average county police force. Unwieldy and underfunded, they are controlled from the centre. And controlled badly

What would a new model Met look like?

I’m not suggesting we go back in time, not least because the past is automatically assumed to be a Jurassic nightmare. Then again, dinosaurs were one of the most successful and adaptable species to ever roam the earth. So maybe – just maybe – it might be worth listening to the dinosaurs. They might have a little wisdom to share.

For example, being a officer working on a local squad in the 1990s was brilliant fun. Yes, I’ve deployed the ‘F’ word. People having fun work harder. We were empowered to work across different levels of crime if it was on our ground. We were given decent kit. We ran operations with little or no interference from the centre. I felt valued, trusted and developed.

Was it perfect?

No.

Was it better than the Met I left in terms of service delivery? By this I mean the the feedback we received from victims and witnesses, as opposed to bald (and inaccurate) statistics.

Hell, yes. I wrote about it here.

Back then, the Met was divided into eight areas, each consisting of a number of divisions. To be fair, there were probably too many divisions, each led by a chief superintendent. For example, the London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea had three. Each area functioned as a quasi-independent police force, with the centre – Scotland Yard – providing policy oversight, governance and responsibility for specialist policing. Call it devolution, if you like, except I don’t remember any Sturgeon-like area commanders demanding independence.

There were pros and cons. There was a massive amount of duplication, with each area having its own training unit, HR, administration and so on. Admin grew like knotweed, occasionally making the 1990s Met a Brazil-type dystopia when it came to bureaucracy. Then again, I’d choose that dystopia over the 21st Century version, which is basically ‘1984’ run by David Brent.

The pros – well I’ve mentioned a few. We also never pretended to be social workers, giving us time to police. One of the most important benefits was areas championed local officers. You could work on a divisional crime squad then move to the area crime squad, anchored in a familiar geographical and cultural space. There were support networks, both formal and informal. Area units had an impressive depth and breadth of work and responsibility.

Then, every time there was a police scandal (and scandals are in the nature of the beast), the impetus was the same. Centralise. Hose out the stables. The people at Scotland Yard knew best. The areas grew ‘smaller’ (i.e. there were less of them) but of course, got bigger (administratively smaller areas had to cover the same amount of real estate, after all). Initially, the MPS was reduced to five areas before adopting a 32-borough model with senior officers adopting a ‘cluster’ each (it’s okay, I worked for the Met and I was baffled too). Now we have BCUs. Mini-constabularies, with the same problems but none of the power, independence or resources to solve them.

The 2000s became the era of police corporatization - local was bad, central was good. It meant control. It meant accountability and uniformity of service delivery (ha ha ha). It was ‘Met-everything’ and it drove me crazy. There was MetHR. You wore a Metvest. Comms were run via MetCall. For fuck’s sake, at the Yard we had a MetCafe. I wouldn’t have been surprised if they’d introduced a MetLoo where you could take a MetPiss.

And so the glittering prize of advancement turned, unambiguously, on the centre. Headquarters. NSY. The place older coppers always called ‘The Kremlin.’ The boroughs? There be dragons.

Then, in the early 2010s, the austerity hammer fell. It was savage. HR, training staff, administrators, intelligence researchers… all gone. Replaced by a call centre or uniformed officers taken off the streets. Where to put them was a challenge too, as they’d sold off the police stations.

The result?

A steady atrophying of skills, experience and morale in local policing. As a specialist, the mantra of every incoming boss was ‘we’re going to do more to support local policing’, except we seldom did. Our bosses spent more time on working groups, or swimming in the shark tank at Scotland Yard, than they did leading ops. Meanwhile, hard-pressed boroughs lost experience and morale plummeted. Even more unfairly, performance metrics were skewed towards local policing, the least loved and (as Casey illustrates) least well-funded.

Talk about being set up to fail.

Ironically, senior officers from provincial forces were increasingly chosen to ‘sort out the Met’, trying to turn the MPS into what many of us scathingly called ‘Londonshire Constabulary.’ Senior provincial officers would look at a map of London and say, “it’s only fifty-odd miles across! When I ran rural-shire it was four times the size.”

Yes, and with less than one percent of the population density, you buffoon.

This led to even more centralisation. Custody units spring to mind. Outside London, a police force might have relatively few custody centres. In London, almost every station had its own custody suite. Why? Well, on average we (1) arrest more people because we’re a huge city, and (2) it takes bloody hours to get anywhere in London traffic; prisoners have to be moved using secure road transport.

The Londonshire crowd not only failed to recognise this, but dug their heels in when it was pointed out to them. By which time they’d be promoted and return to their own county constabularies as chief constable.

Cheers boss.

What if I had my way? My localistic, Auftragstaktik-driven, libertarian streak would return to 8, 10, sod it - 20 areas! Make the Met the world’s biggest-smallest police service(s). There will always be a need for specialist teams run from the centre, but that doesn’t mean mutual exclusion; give local commander the power to run whatever units they feel are necessary. Dismantle the empires who stifle innovation and difference. Experienced officers would return to local policing and share their experience. It’s how I learnt my trade - and another problem identified by Baroness Casey.

Yes, let micro or macro areas have their own dog section if they need one. Or a traffic unit on outer boroughs with fast, dangerous roads. Free CID from laughable Home Office performance metrics. Set up school engagement units and locally-tailored safeguarding hubs reflecting community needs - not Scotland Yards’. A door-kicking tactical team if there’s a problem with weapons, violent crime or disorder. The door-kickers, unlike the TSG, will know the local’s faces. They see them on the street every day. It makes a big difference. A football unit, if there’s a Premiership ground on your patch. You need it? Set it up. Don’t need it? Close it down. Just make sure your teams meet agreed standards - yes, from the centre - and let’s do this thing.

And along with the carrot? The stick. Sack slackers, shirkers and idiots with wandering hands. Let everyone know the score. Give them the privilege of being properly led. As someone who worked for some genuinely excellent sergeants and inspectors, I can confirm it’s a pleasure. There aren’t enough of them, though. Change that and let a million flowers bloom.

Let leaders lead. Let police officers police. And let senior managers do… whatever it is they do. I’m sure there’s a place for them, somewhere.

All I do know is - in my policing utopia - we’d need a lot less of them.

I don’t recall a Commissioner being more universally despised than Bernie Two Dads, and the competition was fierce.

Great article - well-written, funny, and sprinkled with just the right amount of expletives. I remember deliberately spreading a rumour that Hogan-Howe had been sacked after being caught 'en-flagrante' with his horse. Sadly, it never took root.