Senior Met officers launching a departmental restructuring project

The comedy movie ‘Anchorman’ features a bloody gang-fight between San Diego’s TV journalists. Ron Burgundy’s KVWN Channel 4 team battles other broadcasters using cudgels, hand grenades, pistols, tridents and knuckle-dusters. The idea of journalists as feral gang-warriors, fighting for honour and territory is surreal, yet strangely reminiscent of a Metropolitan Police restructuring project.

Well, it used to be; I’ve been retired from the Met for nearly six years. Perhaps things have changed. Anyhow, having witnessed several blue-on-blue gang wars, this week I’m writing about the quasi-tribal nature of police officers, what these cliques look like and what happens when they clash.

Yes, my tongue’s planted firmly in my cheek. And yet…

The Met’s civil wars are usually bloodiest during restructuring projects, combining the tension of a hostile takeover bid with the frenzied bloodlust of a Viking raid. The prize? Prestige and treasure in the form of jobs, land (behold, my liege, floors 13-18 of the Empress State building are now ours!), equipment, remits and – most important of all – budgets to spend on overtime, training courses and vehicles. Oh, and launching operations against criminals. Apparently.

These clan chieftains rise through the ranks, their empires expanding as they conquer weaker departments. The uniform branch are as guilty of this as their CID brethren, by the way; for example I remember the senior alphas of SCO19 (firearms) waging insurgent warfare against any department with the temerity to carry shooters.

This blue-on-blue warfare was usually fought along departmental lines rather than rank. I was struck by the lack of Marxian class-consciousness or solidarity in the Job; coppers tended to identify with their department first and foremost. Furthermore, policing has no tradition of trade unionism - nor in my opinion should it, but that’s another subject. Police are forbidden from taking industrial action, and in any case the political Left are innately suspicious of coppers (my feelings are entirely mutual, comrades). As a result, there’s been little or no attempt to influence the police from that side of the house.

It should also be remembered knowingly causing disaffection in the police is still a criminal offence (why Theresa May hasn’t been collared by now remains a mystery). The Police Federation, so often referred to as a ‘union’ by half-witted journalists, is too often relegated to helpless onlooker.

As a result, internal police disputes can easily descend into Lord of the Flies style free-for-alls. The preferred weapons? Bullying, character assassination, tactical complaints to professional standards and hopelessly skewed ‘reviews.’ Senior officers behaved like all-conquering robber barons, with about as much accountability too.

Met Restructuring Basics; after the review phase is over and the management consultant skirmishers have withdrawn to a safe distance, the implementation team moves in

The most ruthless of these chieftains eventually ascend to godhood, hurling thunderbolts from the Asgards of Scotland Yard and the National Police Chief’s Council. Sometimes this means sacrificing their underlings as they parley with their fellow deities. Naturally, they do this without compulsion – the Met is especially adept at devouring its own. I’ve met senior officers the Medici family would hesitate to invite for dinner.

I only found myself involved in one of these wars, subsequently recusing myself from the rest. I’m not a clubbable person you see, standing by the old Groucho Marx saw when it comes to cliques. I am, however, a keen student of the human condition, one who toiled in the sewers of professional standards – the intelligence and integrity testing units, exposed to the basest of skulduggery (imagined and otherwise). I’ve witnessed this stuff like a mess steward hovering around generals at a peace conference dinner. I’ve heard their table-talk first hand.

DPS intelligence officers getting ready to open the office safe

At this point you might be asking yourself who are these tribes?

In CID and specialist departments, they’re surprisingly amorphous and adaptable groups of coppers. Central to their success is trust – successful policing turns on it. And I mean trust won by deeds, not words. There’s a saying in the Job of timorous souls who bend in the wind: “I wouldn’t follow them into the box,” meaning the witness box at court. Such people seldom find themselves in a tribe.

This loyalty doesn’t necessarily mean corruption, ‘noble cause’ or otherwise (although the record shows on occasion it might). It does mean policing’s tribes tend to include people who roll with the punches. Have a sense of humour. Don’t toss their teddy bear out of the pram when the DI reads them their fortune or throws hurty words at them. I’m sure the last decade has seen a more socially-conscious version, one using the language of social justice and inclusion. Strip away the wellness posters, passive-aggression and rainbow epaulettes, though, and I suspect the dynamic remains quite similar.

Then there’s competence. There’s no point being trustworthy if you’re useless. This doesn’t mean an officer has to be super-cop to be inducted into a police tribe; they value specialists in an organisation which overwhelmingly favours generalists. “This is Dave, he’s shit hot at exhibits and disclosure,” or “this is Suzy, she’s brilliant at interviews,” or (of course), “meet Eddie, he’s great at kicking in doors and sitting in OPs.” Eddie, by the way, will eventually leave the tribe to indulge a burning desire to ride motorcycles on a surveillance team. He’s also great value when he rocks up at tribal retirement drinks.

Tribes are most definitely teams; lone wolves need not apply. Furthermore, a good tribe recognises evolution as the key to survival. This means fresh blood. There’s no ceremony or blood-pact, though. It’s a process of osmosis. Most cops don’t even realise they’re in a tribe until it strikes them one morning, usually after things start going spookily their way.

In return, the tribe supports each other through complaints procedures, promotion boards, divorces, lost court cases, bereavements and subsequent divorces two, three and four. They break bread together, drink together and occasionally fight together – including among themselves. Officers banished from a tribe sometimes became police versions of Ronin samurai or nomad bikers, never to return. I encountered one or two such lonely wanderers, you will completely unsurprised to learn, on professional standards.

At this point, a dirty secret – these cliques were occasionally positive. Yes, they were cliquey (a salty DCI would rock up at a department and, magically, his mates would be in plum jobs within six months) but they delivered results. It’s why senior officers turned a blind eye to nepotism (lower ranks have nepotism, higher ranks have mentoring). It’s all very well running ‘transparent recruitment processes’ (which, for the really Gucci jobs, were virtually non-existent in the Met), but if a department isn’t delivering? It’s time to call in a tribal alpha to solve the problem, followers in tow.

When the system works: ‘The Wire’s’ protagonists, initially outsiders, become a largely benign clique of police officers.

Conversely, some police tribes are fuelled by nepotism and toxicity. The worst are led by sociopathic alphas, surrounded by capable but compliant officers dependent on patronage to avoid the purgatory of local CID. I’ve met detectives who’d sell their souls rather than work sixty-plus crappy jobs chained to a CRIS machine. These alphas are even more driven by ambition than the leaders of other cliques. Their tribes are less cohesive, bound more by self-interest than friendship or loyalty. This isn’t a weakness for alphas, who are only interested in their followers in the context of the alpha’s personal advancement.

Of all the nasty pieces of work you’ll meet during a police career – criminals included – this sort of toxic senior officer is one of the nastiest. Machiavellian and single-minded, they view any disagreement as rebellion and betrayal. They wreck careers like a sadistic kid pulling the wings off a fly. How do they survive? By convincing the chain of command (which is, after all, a self-perpetuating oligarchy with its own toxic alphas) they’re indispensable. Lacking any sense of empathy or shame, they’ll slide the dagger into any officer or department chosen for sacrifice. Then, when they see an opportunity to best an opponent – such as a large restructuring program – the gloves really come off.

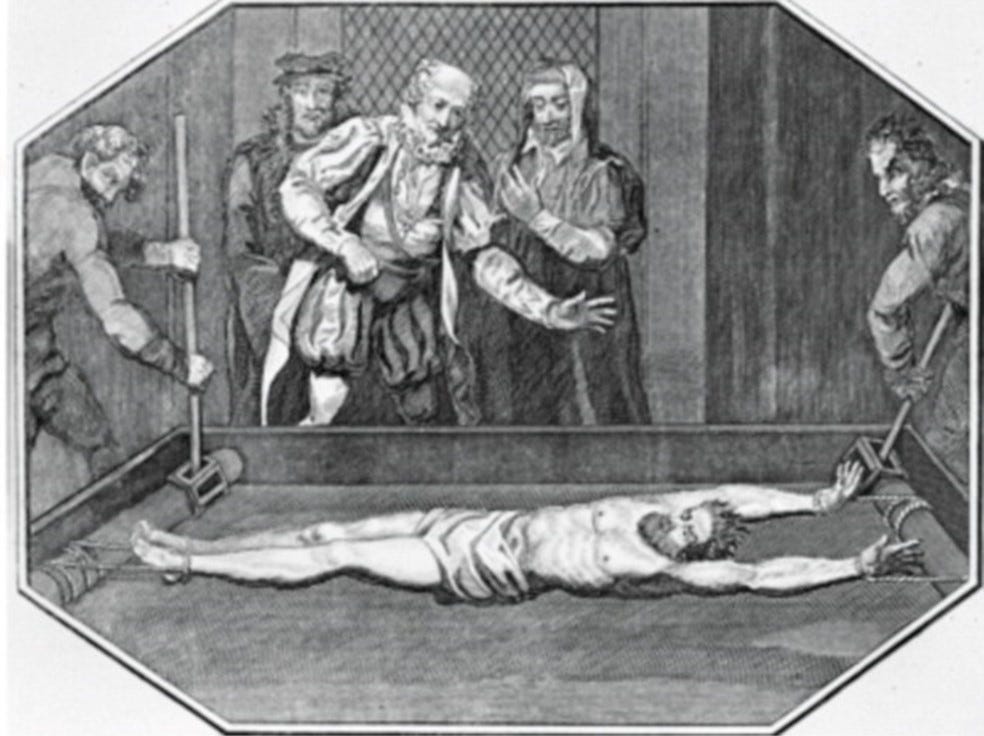

An alpha leads a 360 degree feedback session for an outgoing unit commander

Why do police officers behave like this? Why indulge in messy civil warfare when mature leaders should agree a way forward based on optimal service delivery?

Have you stopped laughing yet?

The truth is I’m not entirely sure; I’m not a psychologist, nor do I have an MBA. And, unlike too many senior officers, I only scored 11/44 on the Hare psychopathy test. I can only tell you what it was like as a bystander.

Let me try anyway. Part of it, I think, might be due to police culture – traditionally a tough, working-class job with no airs or graces. It never left the organisational DNA, perhaps? Many senior officers when I joined had more than a touch of the schoolground bully about them. Or is it due to the innately suspicious nature of police officers? As I’ve written before, everyone lies to police officers, including other police officers. As a result, a certain sort of copper struggles to accept a third party might be acting in good faith. They see plots and plans everywhere, waiting to be ‘had over’ – especially the toxic alphas who judge everyone else by their own shady standards. Punch the other guy before they punch you. Except police don’t punch each other nowadays; they deploy a project team and a management consultancy to screw their opponent instead.

Which brings me to their tactics and strategy. In the military, enemy behaviour suggestive of a course of action is called a ‘Combat Indicator’. If you spot behaviour ‘a’ then you might expect outcome ‘b’. The same is true of internecine police warfare. In my bitter experience, combat indicators of an imminent coup de grâce might include;

An ambitious manager moving to a mundane post

Why is a wily superintendent suddenly taking a dull back-office job in a new department? It’s a combat indicator, of course – his sponsor needs to get him inside the target by any means necessary. Soon the infiltrator will begin placing his allies in key positions as they prepare to seize the airport, presidential palace and TV station.

The ‘Review’

The wily superintendent sends a newly-arrived DI or DS to your weekly team meeting. He or she is friendly, despite a reputation as a cutthroat operator. Your boss nervously explains, “DS Smith is here to write a review for the Commander.” DS Smith smiles like a shark. DS Smith knows you know the real reason. DS Smith has already been given the report (DS Smith isn’t one for writing), which says you’re all crap at your jobs and DS Smith’s boys and girls could do it much better. So why don’t you all fuck off and drive panda cars instead? This is a surefire combat indicator your department’s about to be shafted by the Big Blue Dildo. Sans lube.

You’re invited to a focus group

A middle-manager will facilitate a discussion about the ‘direction of travel’ which is management speak for this is what we’ve decided to do but the checklist requires a fig leaf of staff engagement. You will be trapped in a room with a dry board and a flask of lukewarm coffee and asked loaded questions by a facilitator, none of which will make any difference whatsoever. A senior officer sits in the corner like a gulag political officer, taking note of any potential troublemakers. At this point, people who badly need to stay in post sniff the air and decide to become Quislings. Others begin browsing the intranet for new jobs. Others indulge in gallows humour and decide to join the resistance for shit and giggles.

Management consultants appear

This is a deeply sinister combat indicator, like hearing Soviet artillery on the outskirts of Berlin. The die is cast, the end almost nigh. The management consultant’s job is to rubber stamp DS Smith’s review, the one which wasn’t written by DS Smith. The difference is, DS Smith isn’t paid five grand a day like the creatures from McKinsey or KPMG.

And then…

There’s an announcement

An official email arrives, informing everyone of what they already knew. Now the battle is won, any pretence of faux-chumminess is dropped. A new cohort of grimly hostile seniors are announced, arriving in quick time with their vanguard of tribal warriors. Existing units are disbanded or rebranded, the previous management either taking a knee, Game of Thrones style, or ‘moving on.’ The leadership swiftly conducts mopping-up operations where ingrates identified as resistant to change – or simply because their faces don’t fit – are ‘managed’ out of their jobs. Others are bullied. Most will be given the least favourable postings, expected to gratefully break rocks for their new overlords. You won’t be surprised to learn much of this is facilitated by the Quislings who welcomed their new overlords with open arms.

Total success is announced

The larger the project, the more successful it will be. Any mistake, no matter how large or obvious, is either a teething problem or attributable to the previous regime. This is an iron law of Met restructuring projects, leaders reporting back to Scotland Yard like managers of a Soviet tractor factory.

Then, of course, the wheel turns as the victors become the vanquished during subsequent restructurings. Rinse and repeat. Is a culture of constant change merely a subconscious excuse to justify promotion? All sweaty coppers of a certain vintage witness old ways of working making a comeback, the next generation of tribal alphas pouring sour old wine into shiny new bottles.

As for me?

I found myself on the losing side in a police turf war. I was stupid enough to think I could survive. Eventually, though, I saw the writing on the wall and transferred to another department. A few old colleagues ducked, dived and prospered. Some gritted their teeth and took their place in the salt mines. Others simply walked. The victors cawed like crows pecking at a corpse. There was no happy ending for me. No valediction; the other side won unambiguously.

That’s the Job.

If you don’t have a sense of humour, you shouldn’t have joined.

I do wonder, though, if policing’s conquering tribes expended as much energy fighting the real enemy – criminals – as they did each other, the public they serve would be better off.

Thanks for reading. Next week is all about police medals, hero-grams and commendations, prompted by ex-BBC journalist Danny Shaw’s dig at how much the Met spends (or doesn’t spend) on award certificates.

Well SO12 and 13. Ironically, SO13 (who helped unleash the monster) never saw the *real* victors coming either.

Great piece of writing Dom, possibly based on the demise of SO12?