The long bells - can you hear them ringing?

I once knew a detective inspector who could sniff trouble a mile off. A whisky-scented oracle, he sensed problems before they were even problems. “Can you hear those long bells ringing?” he’d say, eyes narrowed like a frontier scout in an old Western. His decision-making began before anyone else, even if he seldom wrote much down. Such prescience isn’t a teachable skill, requiring years of hard-won experience and rat like cunning. I will return to the importance of this sadly waning police superpower later.

What prompted me to think of the long bells? Matt Hancock, of course. You could sit Matt next to Big Ben on New Year’s Eve at midnight and he’d say, “what bells?” The clown continues to demonstrate Westminster’s shameless hypocrisy when it comes to decision-making. Transparency for you, half-arsed WhatsApp groups for us.

So today I’m looking at how the police are required to make and record decisions - good, bad and indifferent - as opposed to the Cabinet Office circus revealed by Hancock’s WhatsApp dump.

As usual, my bona fides; I’ve helped formulate investigative strategies for the covert phase of proactive policing operations. I’ve applied for too many RIPA authorities, writing business cases for surveillance activities. I’ve worked with Senior Investigating Officers (SIOs), becoming familiar with their decision-making and recording processes. I’ve also made them cups of tea (my superpower). They tend to be busy people.

I took courses at the Met’s detective training school in decision-making for critical incidents and ‘crimes in action.’ I even worked on the Alexander Litvinenko murder for a larger-than-life (but shrewd) SIO, Clive Timmons. I wasn’t always in the office though. I’ve made decisions on ‘the plot’, decisions I’ve had to justify to a judge and jury at the Central Criminal Court.

Mark Bonnar plays D/Supt Clive Timmons in the ITV drama ‘Litvinenko’. A secret: Clive’s a tough guy who really did drive a Porsche, but he likes his tea very, very milky.

In days of yore, detectives concerned themselves with hard evidence, tending to view unused material gathered during an investigation as chaff - this led their decision-making approach. This isn’t to say officers were always wilfully blind to evidence of a suspect’s innocence, but it hardly helped deter confirmation bias either. Then, after a series of high-profile miscarriages of justice, came a timely overhaul of police disclosure processes.

This was the 1996 Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act (CPIA), designed to prevent police from withholding potentially beneficial material to the defence. It also asked questions about decision-making. Why, for example, did officers investigate line of enquiry ‘a’ but not line of enquiry ‘b’? Prior to CPIA, the answer might be ‘because we didn’t.’ After CPIA, that wasn’t good enough. Barristers like Michael Mansfield had burrowed inside the meta of criminal investigation - assuming bad faith - with the mantra, “if you didn’t write it down, it didn’t happen.” If the defence could introduce an element of doubt around police decision-making, the prosecution might lose their case. This meant police had to present defensible decisions to the courts, justifying exactly how and why a case was investigated.

What did this mean for Senior Investigating Officers? Writing. Lots of writing. It also introduced new decision-making models, new case law and an awareness of ‘witness perception’ around tactics and proportionality.

And, yes, keeping an ear out for those long bells ringing.

A complex prosecution case is like a lumbering military convoy, rolling slowly towards the front and, hopefully, a guilty verdict. The defence are partisans, relying on booby-traps and ambushes to derail the convoy. No wonder police officers err on the side of caution along the way, possibly losing opportunities for action as a result.

The result? An SIO has to be a detective, leader, paralegal, tactical and strategic thinker… and a skilled administrator. He or she has to hit the sweet spot between knowledge, experience and judgement. It’s a big ask.

I’m not even joking – this could easily be an SIO with his decision and policy logs.

This doesn’t solely apply to reactive criminal investigations like murders. I remember an article by a senior investigator with the Scottish version of the then Serious Organised Crime Agency (SOCA) who quit in disgust at the agency’s glacial decision-making and risk-aversion. He said, “we’d receive a piece of intelligence and have a strategy meeting. Then another. Four weeks later we were still thinking about it. The bad guys? They’d decide to import ten kilos of coke on a Friday. They were unloading it from lorries the following Tuesday.”

As they don’t say in the SAS, “Who Dares Ends up at a Public Inquiry.”

Decisions are seldom made in a vacuum. For example, if you work for an airline or a healthcare provider, I’m sure you’re used to complying with hundreds of rules imposed by third parties. Policing’s similar but with bells on; officers are especially vulnerable to public complaints, lawsuits, trial-by-media and misconduct allegations. Or even criminal proceedings. These are always at the back of any decision-maker’s mind. It can, on occasion, lead to risk-aversion, a lack of originality and a reliance on investigation-by-checklist.

This is before we consider social media. How do you think that impacts on decision-making? I haven’t even mentioned politics and politicians. I worked on one high-profile job where we were subjected to constant letters and phone calls from a Member of Parliament. Yes, the bosses were mindful of his near-obsessive interest.

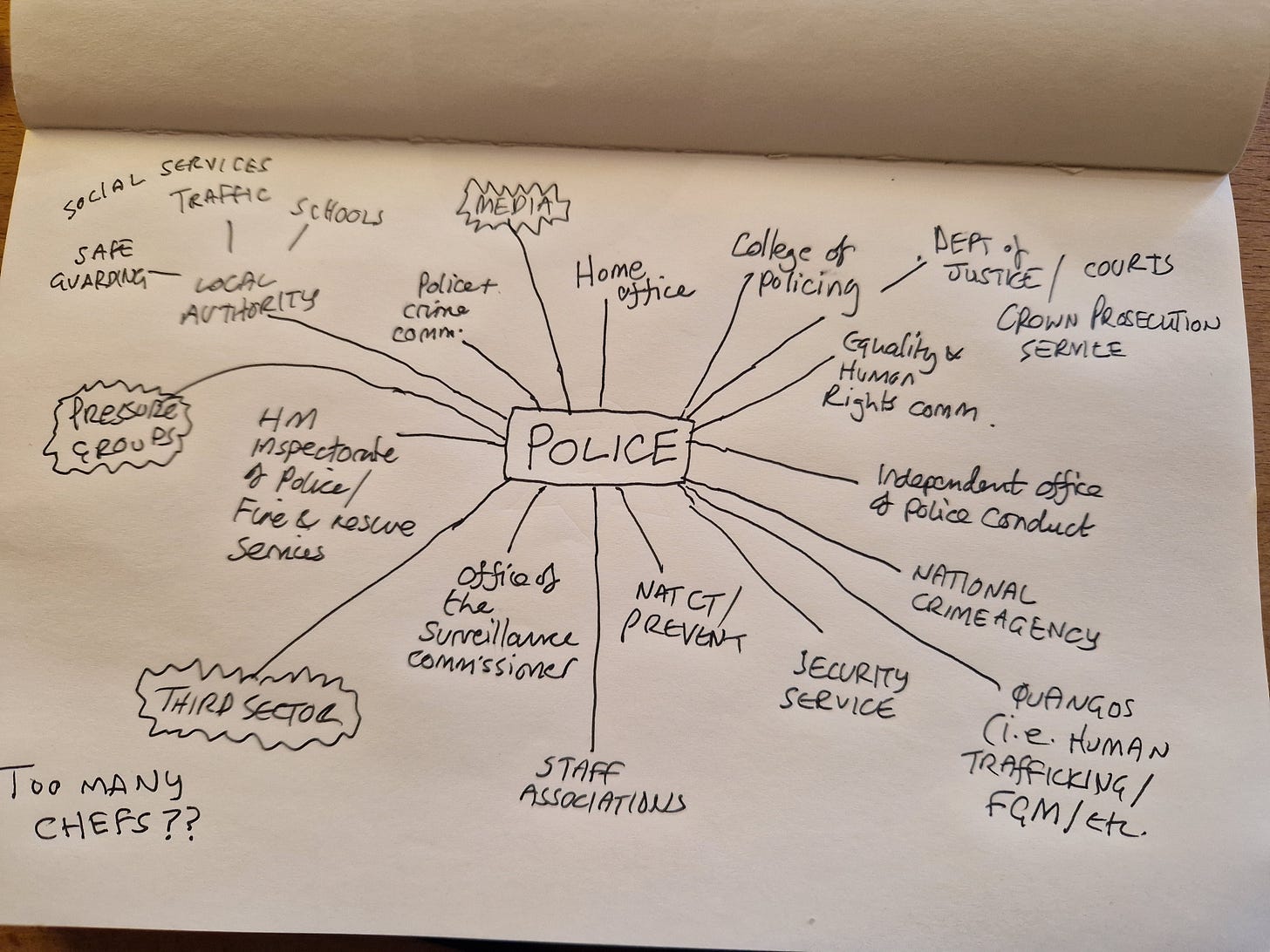

Anyhow, I scribbled a quick diagram of parties to whom police decision-makers find themselves accountable. I’m sure I’ve missed some. Those surrounded by wobbly lines have indirect, but impactive, influence.

The accountability labyrinth.

Then there’s the curse of ‘Riverdance Policing.’ This is a term I heard used by a detective in the brilliant BBC documentary ‘Police Protecting Children’ from 2004 (it’s on YouTube, check it out). It describes the jerky, performative panic that occurs when senior police officers are seen to have to ‘do something’, usually after an excoriating public inquiry. The manic pressure to do everything correctly, belt-and-braces, ends up hindering police activity. It leads to over-compliance and arse-covering. Not to mention pressure on SIOs.

I remember examples of Riverdance policing. Shortly after the Stockwell incident in 2005, detectives on (the then) SO13 antiterrorist branch demanded all original master copies of surveillance images (i.e. memory cards from cameras) were retained, bagged and tagged and never reused – no doubt this made its way into a policy log somewhere. This was when a memory card was sixty quid a pop, meaning our photographers had to buy dozens of new cards every week. Why? In case the defence alleged imagery manipulation. Had any defence lawyer ever made such an allegation? No. But they might! We spent a fortune on memory cards (I won’t bore you with the perfectly good continuity system we used for photographs). To my knowledge, no defence lawyer ever alleged manipulation of imagery offered as evidence at trial. There’s a delicate balance between hearing the long bells and imagining them.

When it comes to decision-making, the police can be their own worst enemy, behaving as if we didn’t operate in a common law environment (my attitude usually erred towards if there isn’t a stated case telling us we can’t do something, then there’s a chance we can). This risk-aversion is called ‘gold-plating’ in the trade, whereby every pen-pusher adds their own layer of compliance to a piece of legislation in order to (a) make it ‘watertight’ and (b) justify their existence. Back-office types love inventing new ways to gold-plate the Riverdance, causing nothing but mayhem and confusion.

None of this helps decision-makers, especially those running complex investigations. On top of their other duties, SIOs are required to keep exhaustive logs detailing their decision-making and investigative rationale. Maintaining these can become a full-time job, putting even more pressure on our plate-spinning SIO. Ultimately, some have to be sub-contracted.

For example, police are required to record thematic decisions. These are called policy logs, outlining the principles behind specific aspects of an investigation. For example, a policy log might outline the SIOs overarching telecoms data strategy. I’ve done this myself, explaining at length why certain telephone numbers from a suspect’s billing are researched but not others. There might be thousands of numbers - it isn’t usually proportionate or even possible to run billing on all of them.

Why do we go to all this trouble?

Down the line, when (or if) a defence statement is received – concocted or genuine – it might turn on a single telephone number. If police haven’t justified why they didn’t research them all beforehand, the defence might demand a full review and a costly data trawl. Sometimes this is a delaying tactic while other defence strategies are prepared. Conversely, it might be part of a quixotic abuse of process gambit – although that might be the accused’s fault more than his lawyer’s. But if you’ve credibly justified why those other numbers weren’t researched ? The judge is more likely to dismiss a speculative application, putting the burden on the defence to be more specific.

Experienced investigators spot these bear traps – hearing the long bells ringing, long before a job goes to court. It’s definitely an art and not a science.

If you imagine my data example is just one aspect of an investigation, imagine how many logs are required for a homicide or a high-risk MISPER? Let alone a multiple-suspect terrorist investigation or the hunt for a linked-series sexual offender. There’s a policy for witnesses. Victims. Forensic strategy. Covert policing tactics and intelligence. Media. Decent SIOs – usually detective chief inspectors* – work the hard yards (they don’t get paid overtime) squaring this stuff away. No wonder so many ambitious officers avoid a role demanding such long hours and reputational risk.

But watching a good SIO at work, like a conductor in front of an orchestra? Except, instead of a string section, they have a specialist firearms team. The doors are blown off their hinges, the bad guys are arrested… it’s a thing of beauty to behold.

So is a problem with police decision-making a shortage of experienced officers, especially detectives? The CID’s no longer a prestigious posting. Furthermore, chief inspectors are modestly paid compared to superintendents, many of whom (in my view) add far less to the organisation than a worth-their-weight-in-gold SIO. Has the role become too much of a tick-box for ambitious chief inspectors moving up the ranks? My serving contacts suggest so. Career detectives who might spend the last ten years of their service as an SIO, after the best part of twenty in general and specialist CID, are virtually extinct.

*In some serious and protracted cases, usually linked murder cases and terrorist incidents, the SIO will be a detective superintendent. Litvinenko is a good example.

The National Decision-Making model. We used to have fun applying it to problems like what to have for lunch.

I genuinely believe optimal decision-making comes from experience. Yes, there’s a critical role for training and professional development but you can’t simulate this stuff. You’ve either taken a case to crown court - the hard way, starting as a case officer - or you haven’t. You’ve either been duffed up by a shit-hot King’s Counsel or you haven’t. A detective needs layers of hard-won experience like a piece of antique furniture needs polish. By the time a detective becomes a good SIO at DCI level, they’ll have taken dozens of cases to court, across all ranks. They’d have won and lost jobs. Gone to appeal hearings. Spent hours arguing their corner in case conferences. Worked cheek by jowl with the CPS and barristers. Used the full range of proactive and reactive investigative techniques. The wannabes – the cops who’ve watched too much TV drama or are ticking a box – would have long fallen by the wayside.

And crucially, to produce a good SIO, you need a cohort of experienced detectives from which they can be drawn. First amongst equals. Every SIO also needs a deputy and case officers - capable DIs and DS’s.

Where will the next DCI Jane Tennison come from?

Let’s get down to brass tacks. Here’s a question; your child is abducted. Who do you want investigating their disappearance and prosecuting the perpetrator? A bright young thing who’d aced every examination to become a direct-entry inspector before coming an SIO, or a career detective who’d served at every rank in CID?

Be honest.

And what happens when the mechanism that produces experienced SIOs ceases to exist? That’s where we are now. And until someone fixes CID, fewer and fewer officers will hear those long bells ringing.

Worked proactive level three crime. We would get 'quick time' intel that wasn't relevant to our remit, but maybe needed a threat to life response or a crime in action interdiction. The people we trusted to take those jobs off us were few and far between, not just because the skills and assets necessary were in short supply (and availability limited), but because we had to trust that we could quickly pass the job and then forget it... it would be dealt with promptly, properly and wouldn't come back to bite us in the arse around disclosure and/or court. We ended up having those working relationships with people who almost exclusively worked proactively.

Proactive bread and butter was difficult real time decision making, without the luxury of endless risk assessment and 'reputational harm' meetings. Our command structure was flatter, and they were confident around making quick (but well reasoned and recorded) decisions. We were all over disclosure and law/procedure because that was what the defence would go for when presented with a 'bang to rights' case. 'Lawfully audacious' anyone?

Not slagging off Reactive units completely, but it did seem they were not quite so sharp and much more risk averse. Much better at golf however.

It does seem that the majority of Police work reactively these days, and I think that does encourage a certain mindset.

A concise illustration of a problem for CID and it’s major investigations, but also most other police activities. Arguably the defence should be given the right to defend the innocent and should be given the benefit of any doubt. Couple this with an overworked, understaffed and cautious CPS it’s surprising anything gets to court let alone a conviction. This results in more criticism of policing and more targets and priorities.....

Whilst I’m glad I’m retired, I do worry about the future of policing.

Thanks for another good read!