The Krays (Reggie on the left and Ronnie on the right): not as good looking as the Kemp brothers or Tom Hardy, are they?

This week Kenny Noye is in the news. Again. Kenny, I think it’s fair to say, is a nasty piece of work. Yet, in the latest BBC drama, ‘The Gold’, he’s been turned into a Robin Hood-style class hero. Not the man who stabbed a police officer. Not the man who told a jury he hoped they all died of cancer. Not the man who murdered a motorist after a petty argument on the M25.

Yes, British popular culture (and the middle-class creatives responsible for much of it) suffers from a blind spot when it comes to criminals. Noble Savage syndrome writ large. Don’t even get me started on the Krays, who spawned an entire industry of true crime hagiographies, the ultimate British gangster-celebrities. I will take the moment, though, to link to one of the funniest pub fights in movie history (warning – NSFW). Even I was impressed by Hardy’s depiction of Ronnie.

Want more? Google the Essex Boys murders if you want to see the enduring level of folklore around British organised crime. In the USA, a trio of drug dealers found dead in an SUV wouldn’t even make a paragraph in the local newspaper – but here? It’s a cottage industry. Noye gets a mention too, having an almost Zelig-like quality in criminal mythology.

My favourite depiction of British gangsters, though, remains the Piranha Brothers.

I could go on, but this article by Ben Lawrence (paywalled) puts it much better than I, lamenting our fascination with horrible bastards like Kenny. For me the acme of the leftish romanticism of criminals is the long-forgotten crime movie Face with Robert Carlyle and (of course) Ray Winston, whereby organised crime becomes an adjunct of frustrated political activism. Check it out. If you can get over the agitprop, it’s a reasonable enough watch.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the political aisle, the arch-conservative and crime writer GK Chesterton once wrote; “The criminal is the creative artist; the detective only the critic.”

Yes, the criminal’s the interesting one; the copper’s merely the lumpen dullard ruining the performance. Unlike GK Chesterton, though, coppers know criminals like David Attenborough watching leopards at a Serengeti watering hole.

So this week, I’m talking about my experience of dealing with criminals. A benefit of spending my service as a Dc was being able to move around in roles chosen for experiential reasons, not because I was playing promotion snakes and ladders. this meant I was privileged to interact with criminals in a way some more senior officers might not. Conversely, I don’t have their experience of leading major investigations.

This subject is also on my mind as I’m writing a crime novel. Yes, I’ll pimp it here sooner or later. In any case, I want – artistic licence aside – my villainous characters to be realistic as possible.

Before I continue, though, a moment for Dc John Fordham, who for GK Chesterton was presumably the critic trying to spoil Kenny’s ‘creative art.’ John Fordham’s a legend in the Met; you see his portrait in more than a few police buildings and social clubs. The MPS surveillance operations room is called the John Fordham suite in his honour. Noye stabbed John to death while he was carrying out surveillance in the grounds of Noye’s house in 1985. Noye claimed self-defence and was found not guilty of his murder. RIP John, who was more of a man – and a hero – than Noye could ever be.

A portrait of Dc John Fordham, who died serving in the Met’s C11 Surveillance Branch

A great deal is said about criminals, often by people working in very specific roles in the criminal justice system. Lawyers, probation officers and social workers come to mind, some of whom might sympathise with the sentiments behind the new Kenny Noye drama. Although these professions spend much of their time with criminals, do they really get to know them? I’ve no doubt they know a version of their clients. Which is to say the version the criminal chooses to present.

It’s their Truth, right?

For lawyers, this might mean, “I’m innocent, or not as guilty as the police say I am.” Lawyers can’t admit otherwise, because they’d be ‘professionally embarrassed’ and heaven forfend a lawyer ever helped concoct a defence strategy that wasn’t true.

For social workers, it might occasionally mean, “I need a sob story for my court report to mitigate my recidivist tendencies.” Too many social workers are programmed to believe this, so little artifice on the criminal’s behalf is necessary.

Probation officers? “I’m trying my best and I know you aren’t professionally allowed to accept I’m beyond redemption. You fucking mug.” The bit in italics is said after the meeting, of course. The meeting that took place after the dozen or so they previously missed. On Zoom.

Come on Dom, aren’t these lazy stereotypes? Maybe, but I was a cop. I’m used to being slapped in the face with lazy stereotypes. I’m just returning the serve on behalf of the coppers who are still serving, agree with me but have no right of reply.

An exception? Prison officers. Screws know the score, because they’re locked up with criminals all day. Okay, too many fall by the wayside. I’ve seen several instances of prison corruption and the extent is genuinely shocking - it makes the police look like a monastic order of virtue. Some of the best writing on criminals I’ve read is courtesy of a prison doctor, Theodore Dalrymple. His experience chimes with mine, especially that most convicts view middle-class penal reformers as fools who they’re able to play like a Stradivarius.

Coppers interact with criminals constantly; I’ve been in the dubiously privileged position to talk candidly with terrorists, paedophiles, a war criminal, bent coppers, animal rights obsessives, drug dealers and every other variety of malcontent. And their families too - I remember a heart-breaking conversation with a gang member’s babymother while taking fingerprints, an insight into a life lived on every conceivable edge - all of them sharp.

I’ve also worked on operations reliant on intrusive surveillance techniques, watching and listening to suspects unaware their immediate environment was wired for sound. Once you’ve heard hardened criminals talking ‘dirty’, it’s always entertaining listening to a barrister in a wig trying to mitigate the conversation in court. Mind you, most decent defence briefs (outliers aside, most of whom do an important job) will advise clients faced with such evidence to roll over, unless they can get it excluded on a technicality, usually via a s.68 challenge under PACE. I’m the sort of nerd who became especially fascinated by Voir Dire and abuse of process trials, of which we won more than we lost.

A covert monitoring post, as shown in ‘The Lives of Others’. After listening to criminals moaning about their partners for hours, it’s a treat when they finally begin talking about where they’ve hidden the drugs

A sociologist might ask; aha, Dom, what precisely is a criminal? Aren’t you using a very broad brush? Which is a fair question, although having suffered ‘A’ Level Sociology (I received a splendid ‘X’ Grade) I stand by the description of sociology as the study of people who don’t need to be studied by people who do.

The dictionary definition of criminal says a person charged with and convicted of a crime. For example, I once met someone with a club number for burglary. He drunkenly climbed into his university refectory after dark and helped himself to a roast chicken. The local constabulary charged him with Burglary under s.12(b) of the Theft Act (those who’ve taken the sergeant’s and / or detective’s exam will be now wracking their brain over 12(a) and (b) and all of the wacky scenarios whereby you might or might not have committed a technical burglary). “That makes me a criminal, right?” he asked. [Edit - a reader pointed out it’s actually s.9 of the Theft Act. Bloody coppers. Pocket Book Rules apply on this Substack so I have to show all my corrections]

Well, technically, yes, he’s a criminal.

But then again, to me, he isn’t. Not really. He did something stupid (albeit mildly amusing), put his hands up, took his punishment and moved on. That isn’t a criminal – that’s someone who made a mistake.

No, I’m not talking about people like him. I’m talking about proper criminals. People who choose ‘The Life’, whereby they make a living outside the law. I also mean people whose personal proclivities (possibly sexual or political) mean they’re forced to operate a certain way to avoid getting caught. I include terrorists in this definition, as I spent a sizeable part of my time working in the interface between policing and the intelligence services.

Yes, criminals range from habitual but petty thieves… all the way to Pablo-bloody-Escobar. Yet they’re all living The Life in their own special way.

I’ll give you an example. One morning in the mid-1990s a long-haired, suntanned man presented himself at the front counter of our police station. I’ll call him Douglas. He was a drug dealer who’d absconded from prison eight years earlier and wanted to give himself up. It was a surprisingly easy process; our duty officer rang the prison governor, who asked us to drop him at Pentonville (easily the most horrible London prison I’ve set foot in, it makes Belmarsh look like the Four Seasons). We sat Douglas in the van. He asked if he could smoke a cigarette. Back then, only an utter monster would deny a man going to Pentonville a smoke.

Douglas’s story was interesting. He’d been a teacher, but by his own admission was lazy with an aversion to kids (like a few teachers I’ve met). He fell into dealing cannabis and due to a new-found enthusiasm for commerce found himself knocking out kilos. He was a cut-price Howard Marks, I suppose, a ‘Mister Nice’.

Why can’t we all be friends? The real Howard Marks, ‘Mister Nice’, with a load of TSG officers at the Notting Hill Carnival in the 2000s.

The problem was, Douglas wasn’t cut out for the more, er, kinetic elements of the trade; the double-dealing and violence. He finally found himself locked up for twelve years (it takes a lot of puff to get that sort of sentence). He served four years, was let out on day release and promptly legged it to Thailand. Then, eventually, he gave himself up. “I wanted to come home,” he said, accepting another Silk Cut and tucking it behind his ear. “That means doing my time. I’m tired of waiting for a knock on the door.”

“What then?” I asked, intrigued by his story. “Will you go straight?”

“Easy son,” he smiled, raising an eyebrow. “Am I under caution or what?”

Of course Douglas wasn’t going straight. I imagine he downsized and stayed under the radar. He reminded me of many drug dealers, especially those who play in the wacky world of weed. Educated. Clever. Charming. Not overly enamoured of hard work. Equipped with a moral compass, yes, but aligned on a slightly different axis.

I liked Douglas. In my mind’s eye he’s living in Cornwall now, selling homegrown puff to surfers and living a quiet life.

On the other end of the scale was someone I’ll call Malcolm, who popped up on the radar during several jobs I worked on. Malcolm liked golf, flash restaurants, prostitutes and scaring people. He needed ‘respect’ like a junkie craves smack. His relationships were, by any objective standard, dysfunctional. Malcolm fell into the stereotype people will be familiar with from watching TV drama - a violent bully, occasionally capable of a bearlike sort of charm. In fact, given his love of ‘The Sopranos’ it begs the question; was Malcolm trying to be the star of the gangster movie playing in his head?

Unlike Douglas, Malcolm was never scared of the knock on the front door, which happened not infrequently. It fed his sense of being an outlaw. An outsider. A proper person. Malcolm wasn’t from a particularly impoverished background either, but pretended he was. It was like he was a human jigsaw puzzle and the most important piece was the need to be a player. He fulfilled the role he’d chosen with ruthless singlemindedness. A shrink would have a field day with Malcolm.

Malcolm would never make it in any kind of ‘civilian’ employment. He was too lazy, too proud and too impulsive. If Malcolm wanted something, he’d take it. The concept of deferred gratification was alien to him. He’d dabbled in every area of crime, from drugs to firearms to extortion. A human claymore mine, known to all but friend to none.

His hinterland? Soul music. He was an expert on Lionel Ritchie. He could talk for hours about golf, obsessing over old tournaments and the likes of Arnold Palmer and Nick Faldo. I even wondered, having some experience of the subject, if his obsessive nature and misunderstanding of social cues was indicative of ASD.

Malcolm’s still in prison, I think. He’s in his mid-sixties by now. I wonder if he needs an agent? There’s probably a market for his story.

Here’s the thing, though, about criminals. About people in The Life: Douglas and Malcolm would understand each other. They’d coexist. Put them in the same room and each would divine the others place in the pecking order. If Douglas showed Malcolm the requisite level of respect, they could do business. Douglas knows when you choose The Life, you can’t always decide which dogs you lie with. Fleas are part of the deal.

Quid pro quo. In for a penny, in for a pound.

This, I’ve learnt, is one of the major differences between criminals and the rest of us. Knowing when to walk away from something wrong. To not break that diaphanous barrier we call morality. Once you’ve done it, it’s easier to do again. And again…

I’ve also learnt whatever the commodity or crime (be it drugs, guns, trafficked women, rape, equities fraud or terrorism), criminals consistently assess risk based on a different set of criteria than the average person on the street. This audacity - this yearning - is their strength. And for a criminal investigator, it’s also their weakness. I’ve met several Flying Squad detectives who’ve told me of armed robbers they’d arrested who said, “I knew I shouldn’t have gone to work today, I had a bad feeling.”

But they did it anyway.

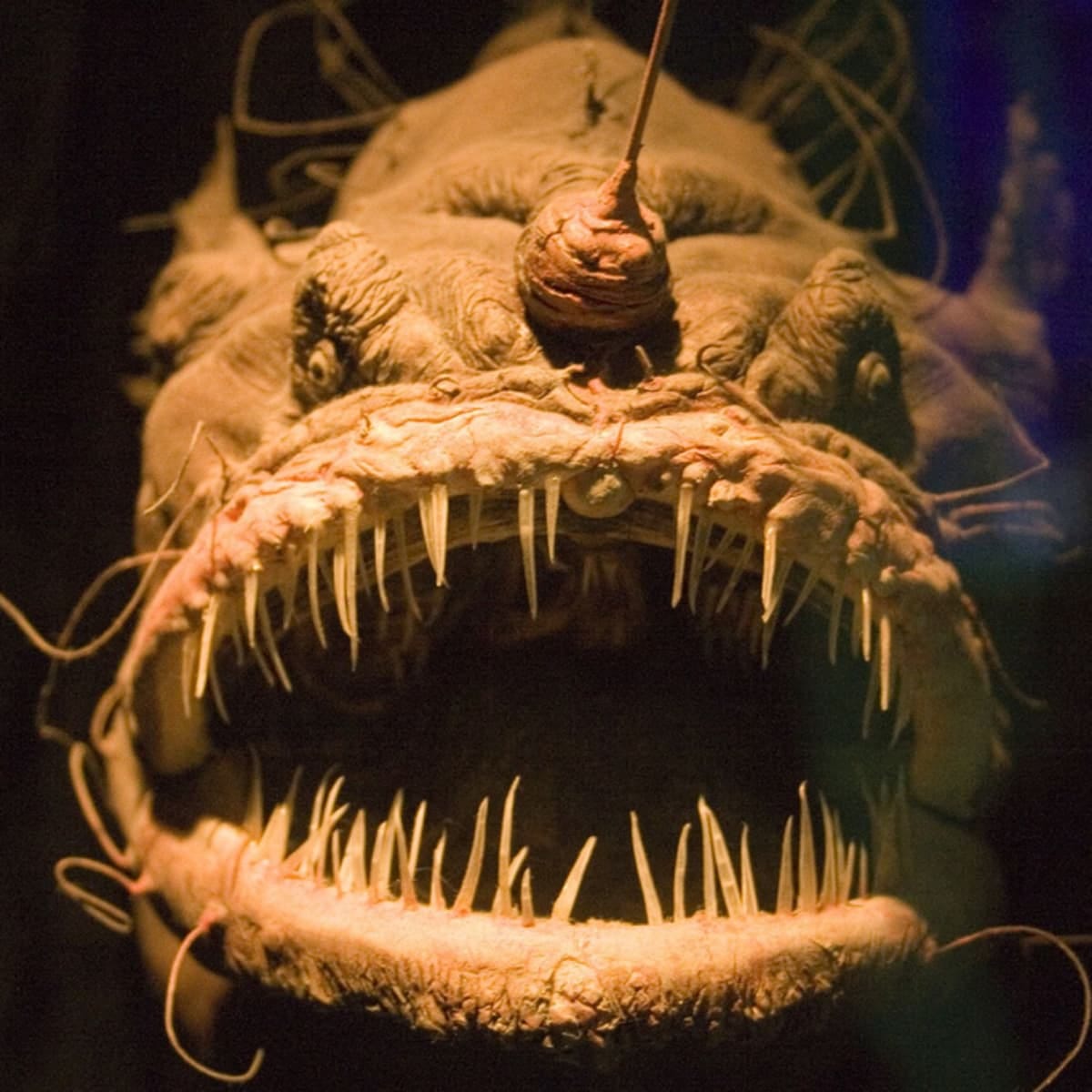

I know something else, too; there are criminals we don’t know much about. They’re like those crazy-looking fish living at the bottom of the sea, creatures we only glimpse using the most advanced imaging techniques. They’re too clever to surface. Too content in their subterranean ravines and canyons. Or the Darknet. These are the criminals who know when to say no. Quietly professional. Top of their game. Indifferent to being ‘A Face’.

They’re out there

Those are the criminals who scare me. Not attention-seeking reptiles like Kenny Noye.

Note: ‘Malcolm’ is a composite. Many coppers reading this will, however, undoubtedly have met him.

The lovable rogue.

Except, they’re generally not.

Did I miss humour in relation to your burglary story? Sec 12 Theft Act 1968 is TDA, 9 (1) (a) and (b) relate to Burglary.