Sir Mark Rowley, Met Commissioner and poisoned chalice enthusiast

This week, thoughts on Baroness Casey’s report on the Met’s misconduct system. The response has been grisly; headlines accusing the service of harbouring a legion of cops with a history of appalling behaviour towards colleagues and the public. Sir Mark Rowley has issued an email warning officers about ‘banter’, which is now a potential sacking offence. I suspect there won’t be many jolly Christmas parties around the Met this year.

Before I throw in my tuppence, my bona fides – I worked on the Met’s Directorate of Professional Standards for five years, primarily in anticorruption. This differed significantly from misconduct; we proactively investigated crime committed by police officers as opposed to workplace behaviour – misconduct is the low-level Cinderella of the professional standards world. That’s why it’s farmed out to Basic Command Units to deal with (known as Local Professional Standards Units), for reasons of subsidiarity and proportionality. However, if you don’t deal with the small stuff properly, it has a nasty tendency to grow into big stuff. Broken windows theory, right?

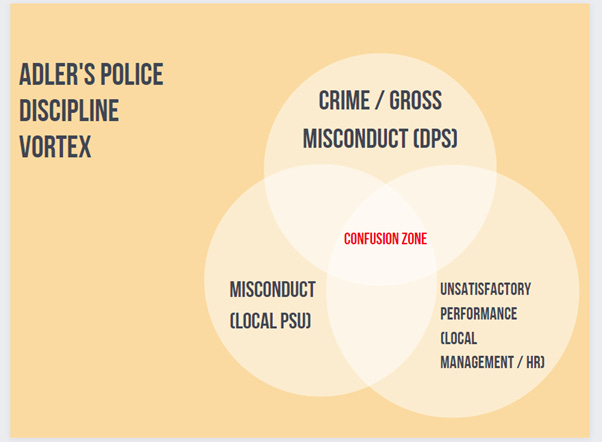

Although I left DPS ten years ago and retired from the MPS in 2018, Casey’s report seemed spookily familiar. What struck me in particular was the ongoing confusion over three overlapping themes in police misbehaviour. Here’s my snazzy Venn diagram, which won’t be appearing on DPS PowerPoints anytime soon:

The discipline vortex: Gross Misconduct, as opposed to simple Misconduct, is a potential sacking offence and therefore escalated in terms of investigation.

As you can see, the Met has delineated areas of responsibility for discipline. The problem occurs when poor behaviour overlaps one or more of these categories, whereupon management decision-making comes into play. At this point, Brendan Behan’s dictum springs to mind; “I've never seen a situation so dismal that a policeman couldn't make it worse.”

Police officers aren’t HR managers. On the other hand, ‘civilian’ HR managers deal primarily with career development, postings and unsatisfactory performance. Are they best placed to deal with misconduct issues? I’d create teams composed of both working together to solve the problem, but hey what do I know?

Although in my day many police HR staff were perfectly competent, there were outliers (one was known as ‘Claymore’ because she was anti-personnel). And as much as the Job denies it, there remains a them-and-us attitude between sworn and unsworn police employees, with some police staff enjoying the fact they technically ‘outrank’ the great unwashed in uniform.

From a police officer’s perspective, this is very much a ‘have you walked in my shoes?’ issue, whereby cops have little faith in decisions made by unsworn civilians. After all, police officers do occasionally receive tactical and malicious complaints, including from colleagues. In any case I think the Met has outsourced most of its HR functions (Dial ‘1’ for arbitrary misconduct decisions…).

The system’s also hobbled by inconsistency when applying discretion. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of discretion but I saw too many occasions where ‘case disposal’ wasn’t about efficacy but convenience. ‘Gripping’ a bad police officer – for any of the three reasons in the diagram above, let alone the Confusion Zone – is an administrative nightmare, the product of a system that still doesn’t know quite what it is.

The Heath Robinson police misconduct apparatus still retains paramilitary elements, with officers wearing tunics and medals scurrying off to Tintagel House (now it’s the Empress State Building) for the Job version of a court martial. I’ll never forget seeing a Pc throwing his guts up over Vauxhall Bridge before his Central Discipline Board. On the other hand, Unsatisfactory Performance Procedure (UPP) is meant to be dealt with in a bean-bags and no-surprises type way. Someone’s suspected of misconduct? What a pain, I might have to apply due process. I know, let’s UPP them and get rid of them that way!

Sir Bill Morris was called in to square this circle back in the 2000s and came up with a commonsense set of proposals. On DPS we worked to a ‘Morris Principles’ plan, but like most Met projects it became a slow-moving promotion vehicle for officers riding the magic roundabout of advancement. Re-reading Morris the following caught my eye, confirming the issue isn’t new; DPS must refine its practice in relation to maintaining policy files, so that the reasoning adopted by the relevant officers for decisions made in investigations is properly recorded.

The inability or reluctance of police managers to (a) be transparent and (b) take responsibility for decision-making also makes life worse for good leaders. A friend, an outstanding sergeant, was dealing with an underperforming probationer on a busy response team. The probationer was incapable of operating safely on the street and a danger to themself and others. This officer was duly gripped by my friend – at which point the Reg 13 procedure for probationers kicked in.

My friend’s inspector realised she was one of the few sergeants on the Borough with the character necessary to sort out underperforming officers (who tend to make allegations of bullying in return, making the sergeant’s life difficult). And so, before long, the sergeant was given more underperforming probationers to deal with. This escalated to the point where her experienced constables began complaining about carrying deadweight officers. The result? The sergeant spent more time writing up poor performance paperwork than leading her team on the streets.

Shame on those inspectors without the balls to manage people properly, many of who are now probably Superintendents and higher.

The toxic police promotion system doesn’t help, requiring as it does evidence of managing misconduct to get signed off for the next rank. In some cases this leads to supervisors actively looking for reasons to discipline officers, or to formalise issues that would usually be dealt with informally – only chickenshit stuff, of course. Dealing with real wrong ‘uns is hard graft. One staggering case allegedly saw a temporary inspector and sergeant effectively fit-up a constable. They hid court warnings so he’d miss criminal proceedings. This gave both the opportunity to evidence ‘managing’ his tardiness.

Neither was dismissed.

Here's another example of the ‘Confusion Zone’ in action; an officer takes a police vehicle home to move his or her stuff to their new flat. Question: is this a misconduct or crime matter (because, technically, that’s Taking a Conveyance)? Do they deserve a quiet word, or ‘sticking on’ (the police term for being reported).

This is where decisions are made without much consistency and occasionally based on whether local management sought to (as they say in the Met) ‘do the officer’s legs’. This is why police officers don’t trust the system – because some managers use it for score-settling. It can lead to relatively minor instances of misconduct being escalated for some, but ignored for others.

Anyone who says this doesn’t happen is, and I’m being charitable, being wilfully ignorant.

The result? An ethical negative feedback loop. An example; Officer ‘A’, who performs well (or is one of the sergeant’s mates), occasionally claims a few hours overtime he hasn’t worked. A blind eye is turned. Officer ‘B’ copies ‘A’ but is sitting in the Inspector’s crosshairs for being gobby or difficult or lazy (or a combination thereof). Ah, but the Inspector can’t discipline ‘B’ because if he does ‘B’ will report Officer ‘A’ for getting away with the same thing. So the Inspector waits for Officer ‘B’ to do something else wrong so he can escalate it, ideally with DPS (so someone else can stick the knife in).

Welcome to the Police.

My take? It’s partly cultural and to a certain extent inevitable. Coppers learn early in service that truth is malleable and honesty’s a moveable feast. Duplicity is like oxygen; everyone lies through their teeth to the police. They learn this from the streetwise criminals who operate with impunity. They learn from the slippery lawyers who routinely prove night is day and Tuesday is Thursday, winning cases when the dogs on the street know the accused’s guilty. They learn from their leaders and peers, who spout shameless bullshit about performance for the media and politicians. They learn every system can be gamed or used to someone’s advantage. Or, of course, weaponised. Police officers quickly morph into avatars of cynicism, shaped by a reality nobody wants to talk about. And they know if anything goes wrong they are pawns in a much bigger game.

The miracle is despite this there really are a majority of honest coppers trying their level best. There are. I’ve seen them and worked with them. And the system doesn’t work in their favour. They’re wading through treacle every day to do their jobs in a world where policing by consent has become a sick joke and every arrest a potential YouTube scandal.

Ugly, isn’t it?

It should come as no surprise officers don’t trust their leaders or the systems they create. As Sir Bill Morris pointed out in 2004:

We are concerned by the apparent failure of the organisation to learn lessons when investigations go wrong. We suspect that one reason for this is that officers of senior rank seem consistently to avoid accountability for either their actions or those of the officers under their direction. We have not heard of any officer of ACPO rank, with responsibility for any of the cases we have considered, being subject to any sanction for failings in the way the investigations were handled.

The fish rots from the head, and the Met’s a veritable Whale Shark. I hope Sir Mark Rowley, when he begins hosing out the stables, starts on the command floor at New Scotland Yard. Will he concentrate on low-ranking officers being horrible on WhatsApp, or the chronic problems with police recruitment, retention and leadership? I think we all know the answer. Think about the news cycle, right? At this point I’m going to take a deep breath.

So here are the headlines from Baroness Casey’s report and my (initial) thoughts;

The Met takes too long to resolve allegations of misconduct / Officers and staff do not believe that action will be taken when concerns around conduct are raised

A staffing and systems issue; if someone thinks they’re going to lose their job they’re going to dig in and fix bayonets. The answer? Better resources. Proper leadership and cultural change. Proportionality in sanctions. None of this can happen overnight, so it probably won’t.

Misconduct allegations relating to sexual misconduct and other discriminatory behaviour are less likely to result in a ‘case to answer’ decision

This isn’t my area, but I do wonder if this mirrors other non-police workplaces? Many of these allegations boil down to ‘he said / she said’ scenarios. I hope this is partially generational too, with younger officers becoming less tolerant of inappropriate behaviour, and bolder in reporting it. I’d also urgently review the Met’s rickety ‘reporter of wrongdoing’ policy. Again.

The misconduct process does not find and discipline officers with repeated or patterns of unacceptable behaviour

This has changed over the past ten years, probably due to austerity measures – I remember an officer’s previous discipline record being a factor in decision-making and proactive targeting. I also suspect shifting too much work to understaffed local PSUs might be part of the reason. The answer? Well for starters manage people properly. Then escalate multiple offenders up the DPS ladder and proactively target them.

The Met does not fully support or resource local Professional Standards Units (PSUs) to enable them to deal with misconduct effectively

PSU isn’t a remotely sexy area of business. Saying that, if you made a posting to a PSU mandatory for promotion to any superintendent role it would magically become super-Gucci. There’s also the issue of not allowing detectives to work on PSUs. Detectives are now a super-rare resource because nobody wants to be one. The answer is obvious (make being a detective less crappy). Again, this is unlikely to happen.

The Met is not clear about what constitutes gross misconduct and what will be done about it

The crux of the matter, so thank you Baroness Casey. As I wrote earlier, it’s due to a lack of consistency and, yet again, leadership. I briefly worked on the team that looked after the Met’s anticorruption reporting hotline (the infamous ‘Right Line’ – it was an old fashioned red analogue telephone in case you’re interested). As anticorruption professionals, our job was to take tip-offs about crime, yet 90% of the calls were from supervisors asking fairly simple questions about line management (one asked me what he should do about an officer he thought was faking a cold to avoid coming into work). This led to the surreal situation whereby a detective constable ended up having a conversation with an inspector about how best to manage his or her team. This nonsense was repeatedly fed back into the black hole that is the Met’s organisational learning strategy.

There is racial disparity throughout the Met’s misconduct system / Regulation 13 is not being used fairly or effectively in relation to misconduct

Race remains a ‘third rail’ issue in the Met. A police blogger (I think it was Inspector Gadget) once explained when it comes to officers from ethnic minorities, line managers are more inclined play things strictly by the book to avoid allegations of racism. Which, ironically, is racist. Why? Well, PC Smith (who is white) fucks up. The sergeant gives him a gentle bollocking and sets him on his way. Pc Jones (who is black) fucks up too. The sergeant, fearing Jones might think she’s being racially bullied if she gets a bollocking, goes formal and writes up an action plan. The result is minority officers get channelled into a formal process when white officers don’t. More supervisors from ethic minority backgrounds is part of the answer, but this isn’t simply an issue of white and non-white. Anyone is capable of harbouring prejudices that manifest themselves in the workplace.

So what can the Met realistically do?

Sir Mark’s new anticorruption squad (which I predicted a while back) will find some scalps – there’s no shortage of low-hanging fruit out there. I’d also be interested to know if the WhatsApp trolls are the same people who are misbehaving at work offline.

Will this keep the Mayor, Home Office and Media at bay? Depressingly, it might, as they all possess the attention span of a concussed goldfish. Short-termism is the cancer of public life. When it comes to reform, sticks are all very well but carrots are better.

What should the Met do?

The Met really is in a genuine bind. Ten years of scorched-earth austerity, followed by a rapid uplift of staff, has created a young, inexperienced workforce led by young, inexperienced line managers. They’re poorly trained thanks to the College of Policing (which I’m sure is funded by a shadowy anti-police protest group). Furthermore, the Met backfilled specialist posts in a panic without due quality control (as I discussed here). I suspect this is how Wayne Couzens ended up where he did.

A retired friend recently got a letter inviting him back into the Met, the carrot being he’d receive his police pension on top of his salary until 2025. They want 400 such officers back pronto. That’s a sticking plaster on a severed limb. It’s also aimed at the wrong rank.

Sir Mark, you need 400 experienced sergeants. Sweaty, wily, gnarly bastards.

Right now.

They need to be posted to BCUs as team leaders. They need to be supported by decent inspectors and an effective local misconduct system. Their mission? To set an example to young officers. To show them how to deal with scrotes on the street. And to ruthlessly get rid of those who aren’t up to scratch, without fear or favour.

You’re up against an uncomfortable reality. As I wrote here;

Policing can be a deeply shitty occupation. The toll it takes on physical and mental health is considerable. Increasingly, the personal commitment it demands dwarfs the rewards. Sometimes, seeing the lifestyles of uniformed officers working punishing shifts and being treated like trash (by both the public and management), I’d occasionally wonder why there weren’t more corrupt cops.

We reap what we sow. This Government was warned in 2012 what would happen and they ignored us. Doesn’t a fundamental tenet of conservative thinking turn on the idea that the State’s primary role is to keep it’s people safe?

Don’t make me laugh. This turn of the wheel – as the saying goes – TJF.

Great article, 100% correct. I retired as a DS in 2016 and got the letters asking me to rejoin. When they received little response (no pension payments then) they created a new role, PSI, Police Staff Investigator. I have worked on a MIT now for 2 yrs and, as a civilian i see everything you write about here manifesting itself in real life. We just lost two experienced officers to the new squad. They were tempted away, mainly by the promise of working from home for three days a week. Just spoke to one of them. In her three weeks there she has one investigation.

Hi Dom

Good trains of thought here driven by an experienced engine. Conversations at the moment in a home counties airport as experienced retired Dc's mull over the 'come back to work' letter. One did raise if malicious complaints result in discipline proceedings will one lose their already granted pension? After the discussion all decided thank you but no thank you Mr Rowley... Keep up the good work.