Papers, Please

Policing, The Troubles, Celebrities and the duty-free totalitarianism of airports

HM Prisons notwithstanding, the most repressive place inside the M25 is Heathrow

Imagine a place where the police enjoy unfettered power; one where officers are are allowed to stop and search people for virtually any reason. They wield an exotic arsenal of deadly weapons. They can arbitrarily demand ID. They’re entitled to banish you from a city-sized array of premises, forbidding you from returning within a specified period. They can prevent you from entering or leaving the country, or detain you without charge for ‘security reasons.’ As for due process? The rules are absolute, and the local magistrates take a dim view of rule-breaking.

No, this isn’t Singapore or Beijing.

It’s Heathrow airport.

Airports are an authoritarian’s wet dream. You thought the pettiness of the Covid-era was bad? Bah, that was entry-level bossiness. Heathrow might look like a shopping centre-cum-building site with a runway attached, but it remains a global transport hub of vital strategic importance. A panopticon of duty-free whisky, giant Toblerone bars and full-spectrum state surveillance. Now, I know safety is non-negotiable when you strap hundreds of people inside a metal tube pumped full of aviation fuel. Yet still…

Maybe my reticence is because I’ve first-hand experience of how utterly you surrender your liberties at an airport; I worked at Heathrow as a special branch officer (before 9/11, when things were more ‘relaxed’). Airports make my inner-libertarian have a panic attack, especially when they order me to take my shoes off; it’s the only time I make sure my socks match. I don’t even like flying, although I once turned left boarding a Virgin Atlantic flight; I could be persuaded to travel Upper Class again.

The unlovely Heathrow Terminal One, which closed in 2015. T1 Domestics was the least-glamorous place for SB officers to work. Naturally, I was posted there

Police at UK airports operate under a complex web of legislation, including civil aviation and local bylaws. Infractions against airport rules give police officers powers virtually unthinkable anywhere else. On top of this, special branch used to have responsibility for Schedule 5 of the (then) Prevention of Terrorism Act (replaced by the Terrorism Act 2000). This allowed officers to detain people at any port for ‘examination’, in order to investigate any potential links to terrorism.

Nowadays, SB has been replaced by the Met’s SO15 Ports unit, who look after Heathrow, City Airport, Biggin Hill, Northolt and the Port of London Authority (covering the Thames). These aren’t the armed officers in uniform you see patrolling airports. They wear suits and loiter among immigration officers at the international terminals, watching for ‘subjects of interest’ passing in and out of the UK.

When I worked at Heathrow (1996/7) there was no Border Force. No biometric passport systems. Just civil servants, VHS CCTV cameras and rubber entry stamps. Special Branch, notoriously aloof, fell under a different chain of command from Aviation Policing at ‘ID’ (the code for Heathrow police station). Formerly the British Airports Authority Constabulary before being subsumed by the Met, Heathrow was a force within a force, with its own dog section, firearms units, CID and traffic department. You’d occasionally meet officers who’d joined straight from training school and retire from the place thirty years later, having never policed a street beyond the perimeter.

Perched on London’s westernmost fringe, ‘ID’ was considered notoriously insular. I remember, as a uniform Pc, being sent to Heathrow on emergency aid after the IRA attacked the place with mortars in 1994. In the canteen at ‘North Side’ (Heathrow Police Station) local officers erected a screen to separate them from the non-airport hoi polloi. Strange bunch.

When I worked there on SB, the local officers seemed amiable enough. Some would visit our office to loaf and cadge cups of tea. Occasionally, when we arrested people directly off a flight, they’d turn up with dogs to support us. Interestingly, bad behaviour on aircraft seemed rarer back then. I have no idea why, as airlines were far more generous with booze in the 1990s.

‘P’ Squad officers, as the SB ports unit was known, attended a course run alongside the Security Service. We were taught how the POTA worked and given presentations on different terrorist groups. SO13 anti-terrorist branch officers taught us how to take comprehensive fingerprints using old-school block and ink (after the IRA’s Brighton bomber was caught due to a partial fingerprint on a piece of card, specialist fingerprinting techniques became mandatory for terrorist suspects). Each terminal kept a special fingerprinting kit in the office safe. We were also inducted into other mysteries of airport skulduggery, which I’m not able to discuss for obvious reasons.

Old-school fingerprinting; ports officers received special instruction for taking terrorist suspects’ dabs

SB Ports officers had a number of duties peculiar to international travel - for example we were responsible for children taken abroad unlawfully by estranged parents. We were given instruction on spotting fake passports and travel documents. You’d meet immigration and customs officers, who’d show you the infamous ‘frost box’ (the transparent toilet drug smugglers were provided with, to see if they’d swallowed packages of drugs). Sometimes other police units would call, demanding we ‘secure the ports’ (ha ha), which is nothing like the movies. Yes, port warnings could be issued on individuals, but in my day it was difficult to track movement through the UK’s increasingly porous borders. We tried. Sometimes we got a result. Sometimes we didn’t.

Our bread and butter, though, was mundane - stopping people boarding or disembarking flights, checking to see if they were worth ‘examining’. As I worked on the domestic gates servicing the Island of Ireland, this meant monitoring people linked to paramilitary groups. We had an analogue phone in our office with a secure line to RUC Special Branch, who would run intelligence checks for us at any time of day or night. If we formally detained anyone, a special team at Scotland Yard - called the National Joint Unit - would be informed. They monitored our work (almost like a remote custody sergeant), ensuring legal niceties were observed. Many people were stopped, but relatively few detained to the point where NJU needed to be informed.

Now, here’s what I think is interesting; as I said earlier, this was an extremely permissive policing environment. We could legally stop anyone. Sure, we occasionally received a complaint, but most were ‘political’ inasmuch as people were complaining about terrorism legislation rather than the officers enacting it (as they were perfectly entitled to do). I’ve met many, many Bolshie folk during my time coppering, but few as self-righteously furious as Sinn Fein activists indulging in a spot of ‘standing up to the bully boy Brits’ cosplay.

So who did we stop, and why?

We sometimes received profiling material, especially areas of interest in Northern Ireland (village ‘a’ or postcode ‘b’). Occasionally we were given specific people to stop. We checked people flying strange schedules or on short trips. People transiting to certain third countries were of interest. Some people would try and board with only minutes to spare, thinking they wouldn’t be stopped.

They were wrong. Step this way, Sir / Madame.

And yes, we stopped people on gut instinct. The older officers posted permanently to the airport, called PCOs (Port Control Officers) were particularly good. One, a special branch legend, was a safari-suited veteran of the Royal Matabeleland Police whose ‘hit rate’ was the most impressive on our team. I asked him what he looked for when stopping a passenger. He was a slightly eccentric character. “I look at their shoes,” he said. “Never trust a man wearing grey shoes. Or no socks.” I’m not sure if he was joking, but he could smell villains – I personally watched him randomly stop three passengers disembarking from an Isle of Man flight. When we checked them on the PNC, they were all Wanted. Mind you, back then the Isle of Man had a reputation; a place where IRA operatives and Liverpudlian drug dealers went to keep a low profile.

I’d also add we’d very few performance targets – special branch expected a ‘return of work’ but in my 15 months at Heathrow I was never given a quota for stopping people, let alone making arrests. SB management considered stopping people for the sake of it vulgar. We were also told abusing the POTA would mean potentially losing it. Back then, the Government had to annually renew the Act in the Commons. This meant working at ports could be… sleepy. Police managers hate it when coppers don’t look busy, but for us being busier would have meant inconveniencing people simply to keep a superintendent happy.

My takeaway from this totally unscientific anecdote? If you recruit the right people, give them realistic mission parameters, trust them and (crucially) don’t subject them to arbitrary performance metrics, guess what? They’re more likely to perform their duties proportionately and effectively. Hey, we had a few shirkers and drunks… but this was the Met of the mid-90s. Go to any department and take your pick.

Stopping people who seemed suspicious could lead to us ‘carding’ (requiring to fill out a landing card) people with legitimate reasons for keeping a low profile. There were gay men travelling from Aldergrove for a weekend in Earl’s Court; mid-90s Belfast, apparently, wasn’t a great weekend destination for gay men. Yet their profile – single guys, travelling for short trips carrying little luggage – meant they might well be stopped. Flights on a Thursday from the Republic of Ireland often carried lone women in their late teens or early twenties – a typical courier profile. Except these young women, evasive when questioned, would eventually explain they were visiting an abortion clinic in West London. Abortion was illegal in the Republic of Ireland. I eventually got used to spotting them.

Then there were sex offenders, off to Thailand to abuse kids. You spotted them from the stamps in their passports and their PNC records. I’ll admit to making their lives as difficult as possible (the law around restriction orders for sex offenders travelling overseas didn’t change until 2003). I might even have caused a few nonces to miss their flights. Oops. The only other thing we could do was submit a ports movement form outlining the circumstances.

It also struck me how big airports are like cities, with their own communities, customs and traditions. People marry other airport people. Aircrew, groundcrew, security, cleaners, coppers, baggage handlers… like a remote hilltribe, but with airmiles. Our terminal was home to British Airways, Aer Lingus and British Midland (remember them?). Quite a few police officers ended up in relationships with ground crew. There was an element of camaraderie between us and the airport and airline staff, especially when dealing with difficult passengers – the terminal had several bars and drunks could occasionally be a problem. I felt sorry for the squaddies downing end-of-leave pints before their flight back to Belfast. Some could get maudlin and a bit punchy.

Then, come late November, Special Branch ‘P’ Squad suddenly became the most popular department in the Metropolitan Police. Why? Our Christmas party was attended by hundreds of air stewardesses. You’d get phone calls from people you hadn’t spoken to for years. “Any chance of a ticket, Dom?”

“It’s okay, Reverend, I’ve buried the Tommy Gun.” Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness

Airports are, apparently, meant to evoke glamour. Even in the less-than-glamorous Terminal One, we saw celebrities. The world of politics gifted us The Reverend Ian Paisley, who’d seek refuge in our office to drink tea and pray loudly. He’d get too much stick in the lounge. “I’m Jewish, Reverend,” I sort-of-lied, hoping to be spared a sermon. Paisley, a silver-haired giant, placed a beefy hand on my head. “You’re all the Lord’s children!” he insisted. “God bless the men and women of London’s Special Branch!”

Gerry Adams would pop by, but funnily enough he never asked for a cuppa. Nobody could glower like Martin McGuinness – a man you could genuinely imagine hiding in a loft with a locked-and-loaded Tommy Gun. And nobody could look as tired as David Trimble (who, at that time, was probably up to his neck in what would become the Belfast Agreement). Even the famous Irish comedian, Frank Carson, would pop in to say hello and tell jokes.

Occasionally, Terminal One felt like Rick’s Café Americain in Casablanca, a place where the protagonists of Northern Ireland’s dramas might coexist, even if only as passengers in an airport queue. On the same flight you’d find British soldiers, journalists (Kate Adie once eyed me like something she’d found on the bottom of her shoe), duffel-coated Sinn Fein lobbyists, hoary Loyalists slathered in King Billy tattoos and even normal folk looking to fly somewhere a bit less angry.

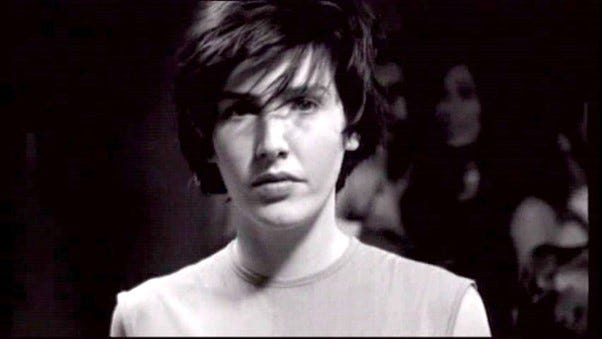

We also had showbusiness types travelling to Belfast and (especially) Dublin. I eventually felt sorry for them, if I’m honest. Airports are depressing bloody places, and celebrities must feel pressured to constantly present their best selves. If they don’t, snarky retired policemen write about it years later. So I’ll start by being positive, as some were jolly nice to peons like me. I once met Sharleen Spiteri, who was flying off to Dublin. I remember her wearing a huge Russian hat with comedy earflaps. Anyway, we ended up chatting. I have no idea why, I didn’t even ask to see any ID. She just struck me as someone who enjoyed shooting the breeze. So did I, so we discussed the tour and the new album (etc). She really was quite lovely.

Sharleen Spiteri, of ‘Texas’ fame and winner of the Adler award for most friendly celebrity 1996/1997

I was also privileged to see the unlikely spectacle of soul legend James Brown eating a baguette in the ‘Upper Crust’ next to the Dublin gate. Surrounded by bouncers, The Hardest Working Man in Showbiz was a vision in tight black leather, stacked heels and bling. He seemed a cheery enough fellow. Then there was a gorgeous Ulrika Jonsson, resplendent in her mid-90’s ladette pomp. She sashayed into the departure lounge in leather trousers and vertiginous heels, her only luggage a designer handbag, a copy of Vogue and a packet of cigarettes. When two burly Welsh guardsmen said hello, she joined them at the bar for a cheeky Stella while she waited for her flight. What a pro!

The Spice Girls? Okay, except for one (you guess who it was). U2? Aloof. Too-cool-for-school. A colleague of mine stopped one of them, insisting his real name wasn’t ‘The Edge.’ Brad Pitt? Disappointingly short. I also think he’s more handsome now he’s older. I suspect he was hungover when I saw him get off a Dublin flight, escorted by an excited-looking Aer Lingus stewardess. It’s a shame Brad was in a hurry, as I’m a fan and ‘Twelve Monkeys’ was released a year earlier - I’d have loved to chat about the movie.

There was also a one-hit wonder pop singer, a stupid young man who waved away an officer’s request for ID. A flunky in his entourage told us, “he doesn’t do security.”

“The wee bastard does now,” a Glaswegian colleague replied, inviting him into our office for a chat about security protocols, good manners and common-sense. The one-hit wonder might also have missed his flight.

There you go: Peace processes. Terrorism. The ethics of untrammelled stop and search. James Brown eating a baguette. Policing is, and always will be, the coexistence of the profound, the mundane and the unlikely. Especially at one of the world’s busiest airports.

I deliberately posted something less topical this week. Something niche. A change is as good as a rest, and I hope you found it interesting. And a special hello to any former Branch colleagues I might have met in the ‘Tap and Spile’ while conducting urgent aviation-security related duties (etc).

Have a marvellous Easter weekend and stay safe. I’ll be back soon.

Dom

Another brilliant article which caused me to reminisce. Some of my provoked recollections include:

Frank Carson drinking tea while I told him my wife was expecting to deliver in a few days. “My wife was in labour for so long they shaved her twice” was his reassurance that I’d be able to get from T1 to Watford General in time.

During the Good Friday Agreement talks I had been protecting RIP. A big part of the plan was to ensure the parties didn’t bump into each other between Downing Street, Parliament and the NIO. On arriving at T1 departures at the end of a very long day he popped down the corridor stairs for a natural break. It was empty so I left him to it and as I walked back up the the corridor Martin McGuinness and his leather-jacketed goons walked down past me. I shit myself. It turns out they just had a convivial chat.

I was handed a Russian GRU agent by a uniformed sergeant whom he had approached in a lift at T4. I think he knew he was heading home to a less than cordial repatriation so wanted to spill the beans to whoever would listen. It happened to be me, and spill them he did. He was eventually removed by some colleagues from the place Spectre seem remarkably adept at destroying. The following morning I was marched to a meeting without coffee, let alone biscuits, with the Superintendent at PCO. His photo was on the front of The Sun alongside Eric Cantona drop kicking a Crystal Palace fan (if anyone can dig out the paper I would love to see it again) alongside his full name and story. The inference (it was definitely and accusation) was that I had called up my contact at News International and decided to trade my future career and pension for a few grand while betraying my country. I was highly miffed but felt unable to prove a negative. ‘C’ had called the commissioner personally to complain as I understand it and that isn’t a situation that lends itself to relaxation. Fortunately I had a blinding revelation that immediately got me off the hook and it was never mentioned again. I spotted that it was a colour photocopy of his passport and in 1996 the photocopying budget of the Met wasn’t able to provide more than charcoal Impressionism. As I say, I’d live to see that Sun front page again as I’d live to find out what happened to my Russian friend.

Fantastic Dom, a gentle stroll down memory lane. Funny how the tedium of duties at the airport (well I was based at Ashford International (T4) for the uninitiated) has dissipated like the distant whiff of aviation fuel. Despite everything it was a valuable introduction to life in the Branch, and to some genuinely inspiring if often odd characters and colleagues. Ahh…….Happy days.