The only person I’ve ever shot. And no, it’s not Roy Orbison.

Looking for a story of armed derring-do? Sorry, I’m the wrong guy. How about a wander down memory lane instead? To an old prisoner-of-war camp in Essex, where the Met trained firearms officers back in the day. What was it like to be an entry-level armed copper before 9/11, when suicide bombers only exploded in faraway places like Sri Lanka and Lebanon?

Yes, it’s another one of Dom’s rambling Substacks. Make a cup of tea, add a big old splash of supermarket scotch and pull up a sandbag.

I’ll start with an unfashionable confession; I’ve always been interested in firearms. I enjoy them on an engineering / aesthetic level and (especially) as a nerdy gun-spotter. I know my M-14 SOPMOD from a MP5SD. I love reading online discussions where gun aficionados discuss the merits of 9mm versus .45 ammo. I browse firearms-related YouTube channels (some of them are genuinely entertaining). I also write thrillers and pride myself on getting the details right. I’m similarly fascinated by swords, crossbows, medieval siege weapons and tanks. You’ll not be remotely surprised to learn I spent many hours making Airfix kits as a kid.

I’m also not a violent person. When I volunteered to be a ‘shot’ I’d no plans to become a fulltime firearms ‘ninja’ either. Of course, I was prepared to shoot someone if absolutely necessary. I know, because I ticked the box which more-or-less asked are you prepared to shoot someone if absolutely necessary? on the Met’s Authorised Firearms Officer (AFO) application form.

Besides, I was in my twenties and wanted to be Bodie and / or Doyle. Probably Bodie, as Doyle had a perm. Although I looked more like Nick Frost in ‘Hot Fuzz’ than Lewis Collins.

In the late 90s I was serving in the Met’s Special Branch, which maintained AFOs for armed surveillance and close protection duties. Very occasionally, armed officers were called on to staff observation posts for counter-terrorism operations. At the time, I wanted to join one of the surveillance teams. I’d also been a liaison officer at the scene of a fatal SO19 shooting and knew what to expect.

I was loitering on the 17th Floor of New Scotland Yard one afternoon when someone from training mentioned there were slots available on the basic firearms course. “I’m up for that,” I said. Randomly bumping into people in corridors was the traditional Branch way of career development; it was a department indifferent to occasionally squeezing square pegs into round holes, reasoning something interesting might come of it. The grit in the oyster that might become a pearl. It was an eccentric way of doing business and the mainstream police hated us. When they disbanded Special Branch in 2006, it was like watching a wildlife documentary. One where a lame, elderly gazelle is torn to pieces by a pack of hyenas.

I digress, but I was like there, man.

Anyway, a few months after I applied to be an AFO (and a fitness test so generous even I could pass) I ended up at Lippitt’s Hill.

Lippitt’s Hill. It looks like the sort of place they’d film old episodes of ‘Blake’s 7’

Lippitt’s Hill in Essex was an old anti-aircraft gun site and, towards the end of the Second World War, a POW camp. We ‘d joke how Steve McQueen would probably try to scramble over the fence any minute. The camp was a gently rotting place of Nissen huts and bunkers. Mossy encasements remained the only evidence of the AA guns which threw flak at the Luftwaffe.

I loved it.

There were bashed-up cars for us to hide behind and a razor wire fence to keep angry locals at bay. Some of them hated the police because they objected to the sound of gunfire. A few would actually patrol the wire, trying to goad officers into losing their tempers. Everyone needs a hobby, but antagonising armed policemen seems niche even by my standards. I hope they were even more pissed off by the police helicopters based at the camp, which were much noisier than pistols. Apparently Rod Stewart lived nearby, although I imagine his mansion was sound-proofed. In any case, I never saw an elaborately-coiffured man wearing leopard skin trousers stalking the nearby woods.

The students in my class were mostly from the Diplomatic Protection Group (destined to earn overtime standing outside embassies), the Flying Squad (destined to ambush unfortunate robbers ‘going across the pavement’) and Special Branch officers (destined to loftily keep why we needed guns a closely-kept secret).

Our instructors were salty SO19 constables. Despite their blue fatigues and berets, the training regime was personable and friendly. The only thing guaranteed to rile the instructors were safety lapses. One DPG officer on my course was kicked off for fiddling around with a weapon when told not to. Truth be told, the rest of us were glad; the more time we spent around guns, the more we realised the gravity of ‘carrying’. I’d been an army reservist before I joined the Met and remembered the old saw that nothing was as dangerous as a squaddie with a Browning – the short length of the weapon meant, unlike a rifle, it was easy to point anywhere without thinking.

When I did my course the Met was replacing its venerable Smith and Wesson Model 10 revolvers with probably one of the most famous handguns in the world; the Austrian Glock 17 9mm self-loading pistol.

The Glock 17, an easy-to-shoot weapon that’s a pleasure to fire. The safety mechanism is the second ‘trigger’ just extending beyond the first.

Amazingly, the course was only two weeks. There were no time-wasting breakout sessions or navel-gazing bullshit. Every minute of the day was utilized. Now the course is 6 weeks long, I wonder if that’s changed? We only trained on one weapon, whereas nowadays I believe students cover the MP5 carbine too.

The course concentrated on weapon-handling, marksmanship, law and tactics. We were putting live rounds down the range every day to build skills and confidence. The instructors were patient and professional; I’d no doubt they wanted us all to pass but were prepared to fail people who didn’t make the grade. They were also keen to point out the gravity of being an AFO. “Look, if this isn’t for you there’s no shame in it,” said one. “In fact, it takes a bigger person to admit this job wouldn’t suit them. Shooting people really is shit.” From his thousand-yard stare, I suspected he knew of what he spoke. SO19 officers were often given training gigs while waiting for the aftermath of a police shooting to pan out.

We were also taught how a firearm, for a police officer, is simply another tactical option. We’d roleplay arresting seasoned criminals (played by the instructors) who weren’t even remotely bothered by police pointing guns at them. Students would, perhaps naturally, assume people with a Glock levelled at their chest would be compliant. The reality’s very different, so AFOs were also required to be adept in the use of batons, CS Spray, handcuffs and the Mk.1 open-handed strike. Nowadays police have other kit to think about too – there were no Tasers or body-worn video cameras back then. Camera phones? Perhaps they existed in 1998, but I’d never seen one. Certainly, when anything noteworthy happened, you didn’t see dozens of drooling morons filming it.

The experience was sobering, a long way from the trigger-happy, crayon-munching stereotype coppers love to tease SO19 with. Although the parts of the course I enjoyed most were macho; hard-stopping cars, range familiarisation session with SO19s different weapons (5.56mm HK rifles and MP5s, including the ‘Kurz’). I blew an old car door off with a Remington 870 pump-gun. There’s something primal about recoil, the weapon’s stock biting into your shoulder. The boom of gunfire. The stink of cordite. Seeing the look of glee on my face, the instructor standing behind me whispered into my ear. “Remember, son, you’re getting paid to do this shit.”

We spent hours doing shoot / don’t shoot scenarios, engaging live suspects with Simunition (paint ball-type ammo, fired from converted Glocks). Every shot was discussed, our instructors doing unnervingly accurate impressions of cocksure barristers scrutinizing our decisions in court. We were expected to know the Criminal Law Act s.3 1967 (governing the use of force) by heart.

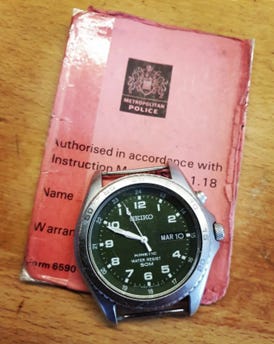

The Met ‘firearms ticket’. You passed the course and were awarded with a… piece of pink cardboard. The Seiko is the one I wore on my course (I collect watches)

This was useful on the video ‘Judgement Range’ debrief, which I’m sure you’ve seen on TV. The 25-metre range (most police shootings occur at short range) was equipped with a video screen which transported you to an American shopping mall in somewhere like Ohio (the people who made the ranges were Yanks). A woman – I like to think she was called Barbara – would shriek as an assailant went postal and you’d decide when, and if, it was appropriate to shoot. The judgement range was a Pass / Fail test.

Some people failed.

These sessions were hotly debated by students and instructors – I can honestly say the ethos behind every engagement was “how could we have ended this situation without opening fire?” This is an eye-opener for many people. For soldiers, engaging with and killing the enemy is a metric of success. For police, engaging with and killing suspects is a failure.

To my surprise, I did quite well on the course (it’s not like I’m a natural at this stuff. I’m not really built for action and adventure). I remember trying extra hard because I’m left-handed and the world of guns is discriminatory towards southpaws. It didn’t help that my right eye is my master eye, either. The instructors spent time working with me to fix the problem, deciding it was better if I shot right-handed. I was used to this; as a reservist I’d trained with the early iteration of the SA80 rifle which is impossible to shoot left-handed (unless you want your teeth knocked out by the charging handle). The problem is, my brain is left-handed. It’s okay on a range, but not when you’re looking for cover during the tactical phase. The toughest muscle to change is muscle memory. I just tried my best, and ended up shooting with either hand depending on the situation.

On my final shoot I scored 98%.

I’m convinced most of that was down to good instruction. Old-fashioned, kind, no-bullshit and occasionally sweary instruction. Praise and gentle bollockings, from people who’d won your respect. Carrots and sticks. Modern-day policing please take note. If you can turn a left-handed, shambling liability like me into a tactically competent, half-decent pistol shot in two weeks you’re doing something right.

Of course, from a training perspective, the Met snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. This was because you only reclassified quarterly as an AFO. As anyone who works with firearms knows, practice is essential and common-or-garden ‘shots’ didn’t get enough time on the range. Finally I went on another posting and someone decided I didn’t need a gun. I haven’t fired a weapon since.

Which is a shame, because I’d love to. Maybe one day.

Still, it’s unusual for a British cop to fire a gun at all. There are only a handful of countries where police don’t routinely carry weapons. Places like Iceland, New Zealand, The Republic of Ireland and… er, the UK (population 67.5 million). Personally I still think it’ll be a sad day when every copper carries a gun. It’s not for everyone and a ‘kinetic’ police force that requires tactical aptitude as a prerequisite will end up with… kinetic cops. That’s not to say there shouldn’t be more armed police, just that not all police need to be armed. Try having this conversation with an American cop, by the way. They think you’re stark raving mad. It’s apples and oranges, guys. You have a Second Amendment and we don’t. It really is that simple.

This stuff is as serious as it gets. I vividly remember an operation where a man was shot dead by an SFO team. Red blood on chalky skin. The tang of tear gas. Frantic first aid, bloody bandages snaking around a policeman’s leg. The small hours quiet. The baggy-uniformed shooter led away by colleagues, his weapon held high in the air. He jogged by my car, a stony look on his face. That officer spent years on gardening leave while they decided his fate. Remember, he volunteered. He did it so other cops didn’t have to, so they could help the public in ways that don’t involve weapons.

All police shootings are, quite properly, controversial. Some jobs are disastrous, occasionally for reasons beyond the control of the poor bastard pulling the trigger. And, of course, there are hordes of people who will never reconcile themselves to anything police do anyway. And to think; these operations take place using trained, professional people. You might not agree, but that’s been my experience. How much worse would things be if we went down an all-armed route? Real-world operations are dynamic and complex and unpredictable. Every mistake is analysed and war-gamed and Monday Morning Quarterbacked, resulting in Tsunami Management which only makes things worse.

We live in an imperfect world. Guns exist and we can’t uninvent them. Nor can we uninvent violence. So I think, broadly speaking, the way we do things is the least-worst option. Sometimes, that’s the best you can hope for.

Especially if you’re a police officer.

People seldom think, the last thing a UK cop wants to do is actually pull the trigger.

Chicken-bone...